Before the Viscount of Alamein, there was Monty of Mount Carmel

A few years before halting the Nazis in Egypt, the irascible general commanded a counterinsurgency from his Haifa HQ

A bit of housekeeping: The generically named “Oren’s Substack” is now going by “Undercurrents” (at least until I change it again). The idea being that there are lots of writers analyzing the news, especially here in this corner of the Eastern Med, but very few diving deep beneath the daily churn. Not current events, but the undercurrents of history still generating ripple effects today. Have I overdone the water metaphor? Anyway, you get the idea.

To today’s post: One reason I started this channel was to bring readers closer to the historical craft. To not just quote from the archival record but to bring those documents closer to you. In the images below you can make out my notepad and pencil, my outstretched finger and my reader’s tickets from archives in London and Oxford. You’ll see my child-like scribblings, and the more disciplined penmanship of one of the great (and greatly flawed) war chiefs of the 20th Century: Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein.

Autumn 1942. It is three years into the Second World War, and the very worst of times for the Allies. Everywhere the Axis tide is rising: from France to Norway to Greece, the Atlantic to the Mediterranean to the Pacific. That spring, German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel had routed the British in Libya and seized the port of Tobruk. Then in summer, in the First Battle of El Alamein, the British Eighth Army fought the fascists to a stalemate but sustained heavy losses. The Nazis seemed primed to take the Allies’ most strategic sea lane — the Suez Canal — then march on to Mandate Palestine and far beyond.

In stepped a little-known, diminutive officer with a brisk step, a brusque manner, a moustache and a black beret: Gen. Bernard Montgomery. At the Second Battle of El Alamein, in Egypt’s Western Desert, British troops under his command penetrated the Axis defenses, forced a retreat, and gained the initiative in North Africa — and the war itself. Over two weeks in October-November 1942 they had pierced not just the Axis line but the very myth of German invincibility.

The triumph at Alamein moved Winston Churchill to utter these famous lines: “This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.”

“It may almost be said,” Churchill wrote in his memoirs, “‘Before Alamein we never had a victory. After Alamein we never had a defeat.’”

Bernard Law Montgomery was born in 1887 in Kennington, South London, to a family of Ulster-Scots gentry steeped in the Church of England and the British colonial establishment. His father, Rev. Henry Montgomery, was an Anglican vicar and later Bishop of Tasmania; his grandfather Robert Montgomery was lieutenant governor of the Punjab.1

His mother Maud’s lineage was similarly distinguished. Her father Frederic Farrar had been Archdeacon of Westminster, but also a keen classicist and philologist with a deep interest in science (he was a pallbearer for Charles Darwin and delivered his funeral sermon at Westminster Abbey).

Married at just 16, Maud was a pious disciplinarian, with none of her father’s more expansive interests. And little Bernard, the third of six surviving siblings, was an unruly child.

“Certainly I can say that my own childhood was unhappy,” he would write in his memoirs. “This was due to a clash of wills between my mother and myself. My early life was a series of fierce battles, from which my mother invariably emerged the victor.”

The beatings, he remembered, were “constant.” Still, he reckoned:

The net result of such treatment was probably beneficial. If my strong will and indiscipline had gone unchecked, the result might have been even more intolerable than some people have found me. But I have often wondered whether my mother’s treatment for me was not a bit too much of a good thing.

At 20 Montgomery enlisted at the officer’s academy at Sandhurst.He was small — just 5’7” — but even then he had gained a reputation as an efficient, demanding, and unorthodox staff officer with an obsession for training and discipline.

In the Great War he was shot through the lung in Flanders and nearly died. After the armistice he married Betty Carver, the widow of an Olympic rower killed at Gallipoli.

Betty was a gifted artist and a lively companion; the first ten years of their matrimony were Monty’s happiest. But in 1937, on holiday in Somerset, Betty suffered an insect bite that became infected. Sepsis set in, her leg was amputated, and her condition declined.

“Betty died on the 19th October 1937, in my arms,” he wrote. “It is hard to bear and I am afraid I break into tears whenever I think of her. But I must try to bear up.”

Years later, Monty’s stepson observed that Betty had kept at bay “those schizoid tendencies engendered by his upbringing which were always latent… a single-mindedness progressing to narrow-mindedness, a detachment leading to lack of human feeling and suspicion of the motives of others.”

In Monty: The Making of a General, his biographer Nigel Hamilton noted that had he given himself time to mourn his beloved wife, “he might have emerged a deeper, richer human being. Instead he swiftly internalized Betty’s memory and got on with his job.”2

The “job,” as it happened, was pacifying an Arab revolt that had erupted the year before in Palestine.

It was to be his second deployment to the Holy Land. A few years prior, in 1931, he had been briefly posted to Jerusalem as colonel of a battalion. At the time, he had written his mother:

It is a wonderful place. In the new city and shopping areas outside the old walled city you have hotels that would not disgrace New York, & you can buy anything you want from a Singer sewing machine to a Rolls Royce car. Then you go through the Jaffa Gate into the old walled city and you pass at once into an eastern city of 1000 years ago or more.

An army performance review from that earlier deployment is telling:

Montgomery. He is clever, energetic, ambitious, and a very gifted instructor. He has character, knowledge, and a grasp of military problems. But if he is to do himself full justice in the higher positions to which his gifts should entitle him he must cultivate tact, tolerance, and discretion.

Now, ahead of his second tour, he was promoted to major-general and given command of the 8th Infantry Division, based in Haifa and responsible for all Palestine’s volatile north: Galilee, the Jezreel Valley and Samaria. He was now 50, but still consumed by a single-minded, restless determination to climb to the army ladder’s uppermost rungs.

In December 2018, while writing my book Palestine 1936, I made a research trip to the UK.

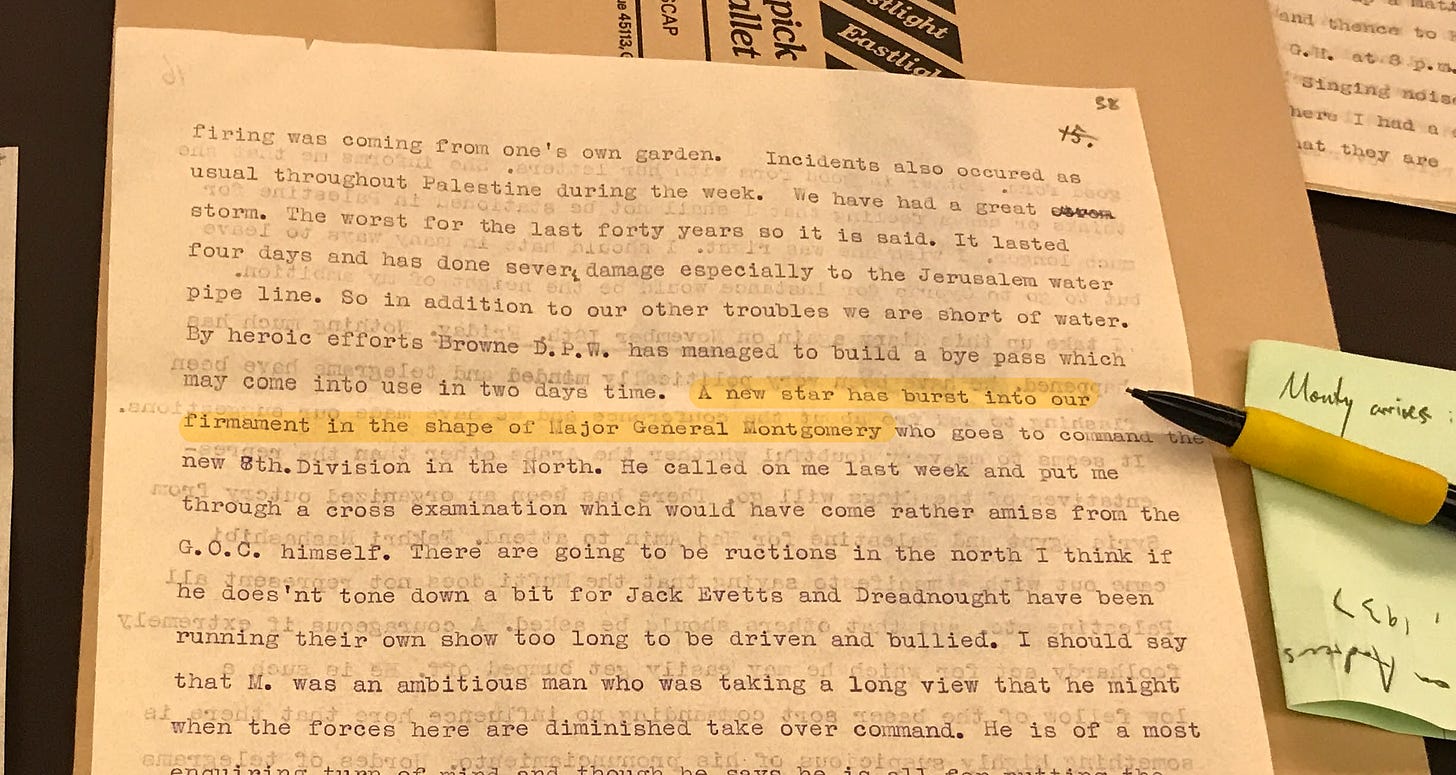

At Oxford’s Bodleian Library I found the papers of William Battershill, then acting High Commissioner for Palestine. His diary of November 13, 1938 records his first impressions of the new arrival:

“A new star has burst into our firmament in the shape of Major General Montgomery,” he wrote. “I should say that M. was an ambitious man… of a most enquiring turn of mind… He is sharp-featured and evidently has a brain.”

“He looks alive and may have real ability,” Battershill observed, predicting that Monty ultimately aimed to take overall command of the Palestine garrison.

“Time will show.”

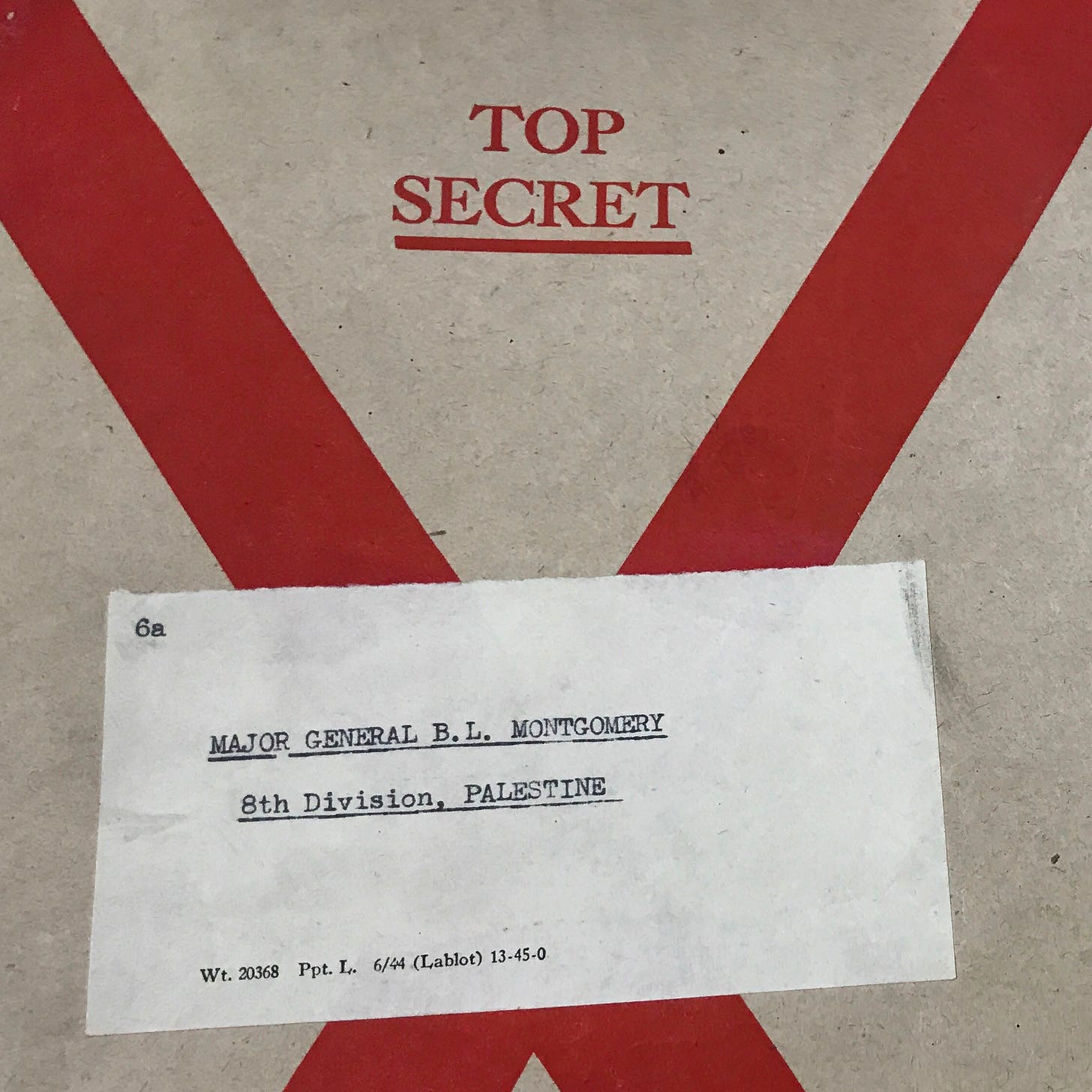

Later, at the National Archives in London, I found Monty’s collected, top-secret correspondence from Palestine.

His first letter, dated December 4, 1938, was addressed to Gen. Ronald “Bill” Adam, Deputy Chief of the Imperial General Staff back at the War Office.

“My dear Bill,” he wrote from Haifa, “You asked me for my views on the situation out here… I will try and set out the situation as I see it.” He claimed he had visited every army post and talked to “every single British policeman” to try to gauge the nature of the uprising.

“I wanted the answer to the following question: Is the campaign that is being waged against us a National movement or is it a campaign that is being carried on by gangs of professional bandits?”

“It began to be clear to me that the campaign is not a national movement. I am certain now that this view is correct.” The insurgency was, in his view, one led by “bandits” — but that did not mean it was to be taken lightly.

“It is important to realize that we are definitely at war.” Armed groups “must be hunted relentlessly; when engaged in battle with them we must shoot to kill. We must not be on the defensive and act only when attacked; we must take the offensive and impose our will on the rebels.”

At the same time they had to do whatever possible to win civilians, in the cities and the country, to their side: “We must be scrupulously fair in our dealings with them... We want them to realize that they will always get a fair deal from the British army. But if they assist the rebels in any way they must expect to be treated as rebels; and anyone who takes up arms against us will certainly lose his life.”

By the start of 1939 he was feeling more sanguine.

The rebels, he wrote Gen. Adam the first day of that year, were fighting like “wild beasts,” but his troops had killed at least 100 over the previous ten days alone. “There are probably more,” he added, “but I take account only of dead bodies actually collected.”3

“The bulk of the Arab population of the country are ‘fed up’ with the whole thing,” he reported. “For the future I am full of hope. The situation is definitely in hand and there are very distinct signs that the rebel movement is crumbling.”

By spring 1939 he was convinced the rebellion was crushed and, with characteristic self-confidence, that it was he who’d done the crushing.

In handwritten comments he titled “Brief Notes on Palestine,” he wrote to Lord Gort, who as Chief of the Imperial General Staff was the army’s uppermost brass (and later, Palestine’s second-to-last high commissioner):

The rebellion out here as an organized movement is smashed; you can go from one end of Palestine to the other looking for a fight and you can’t get one; it is very difficult to find Arabs to kill; they have had the stuffing knocked right out of them.

He added a prophecy for the future:

The Jew versus Arab problem… will go on for the next 50 years in all probability. The Jew murders the Arab and the Arabs murder the Jew… [but] the great bulk of the population of both categories is entirely opposed to it; it is carried out by the young hot-heads on each side.

Monty believed his work in Haifa was done. It was time to leave.

“I shall be sorry to leave Palestine in many ways as I have enjoyed the ‘war’ out here. But I feel there is a sterner task awaiting me at home.”

In a taped interview held at the Imperial War Museum, a former junior officer in Palestine recalled his comrades’ sentiments toward Monty.

“To us he was absolutely God,” said the officer, Humphrey “Bala” Bredin. But “he talked to us not as a very senior officer but as a keen soldier in pursuit of the facts.”

Most Saturdays, he said, Monty would gather half a dozen young officers for supper at divisional HQ, grilling each of them in turn: “‘What do you think of the Arabs?’… ‘What do you think of the Jews?’... We regarded him as a jolly good stepfather. We realized he had studied his profession. It was oozing out of him.”

“We were passionately pro-Monty. I do realize he was a vain man, but he had a great deal to be vain about,” Bredin said. “To my mind he was a great man, who like most great men, had failings.”

He recalled how Monty bade his subordinates farewell.

“When you get done, have a jolly good leave, then get down very quickly to learning how to fight Germans,” he told them. “You won’t have much time.”

Montgomery dove into the war with his usual, limitless energy, playing a key part in the Dunkirk evacuation and raising Britain’s defenses for a potential German invasion.

After the victory in Egypt he went on to lead Allied forces in the successful D-Day invasion of Normandy, and the altogether unsuccessful invasion of the Netherlands in Operation Market Garden.

But his name would forever and always be associated with El Alamein, and in January 1946 he was made Viscount Montgomery of Alamein. Months later, he was named Chief of the Imperial General Staff.

Meanwhile Palestine was engulfed in a new revolt — this time not Arab but Jewish.

The 1939 White Paper severely limiting Jewish immigration to Palestine still remained in effect, even after the full revelation of Hitler’s horrors, even as hundreds of thousands of survivors languished in DP camps. The “Hebrew Resistance Movement” had a measure of support across Palestine’s Jewish community — even the mainstream Haganah joined for a time — but its most militant faction was the Freedom Fighters of Israel, known by its Hebrew acronym Lehi. The British called it the Stern Gang.

The victory at Alamein had stopped the German march east, where the Nazis had already begun drafting plans to annihilate Palestine’s 450,000-strong Jewish community.

But as one of the most iconic faces of the British Empire, Monty now became a target. It was no idle threat, given the Lehi’s assassination of Lord Moyne, Britain’s top representative in the region, two years prior in Cairo.

In his first months as army chief Monty visited Palestine three times. His visits prompted extreme security precautions, as reported in newsreels at the time.

Once he was safely back in London, a policeman was posted permanently outside his flat for fear of a Jewish attack.4 One day his aide answered the phone and heard a threatening voice on the other end. According to Monty’s memoirs, the conversation went like this:

Is this the War Office? This is the Stern Gang speaking.

Good evening. What can I do for you?

Tonight, for the Field-Marshal, a bomb.

Thank you, I will let him know.

Are you trying to be funny?

No — I thought you were.

In one of his pre-war letters from Palestine, Montgomery had written this:

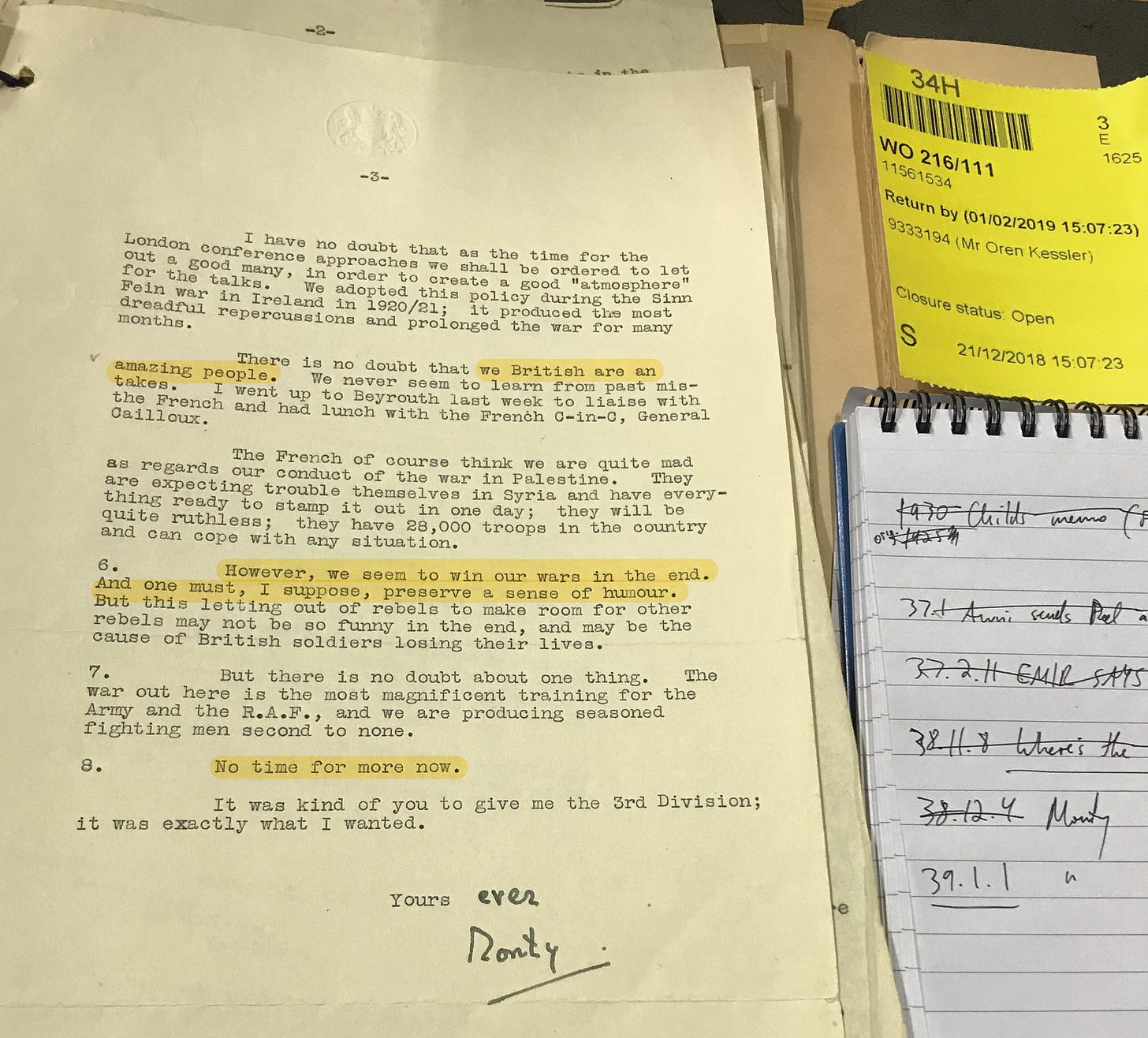

“There is no doubt that we British are an amazing people. We never seem to learn from past mistakes... However, we seem to win our wars in the end, and one must, I suppose, preserve a sense of humour.”

“No time for more now,” he signed off with typical haste.

“Yours ever, Monty.”

Sahiwal, a city of half a million in modern Pakistan, was founded in 1865 by Robert Montgomery and was known as Montgomery until 1966.

Hamilton speculates: “There can be no doubt that, by temperament and inclination, Bernard Montgomery was disposed towards the male sex rather than the female; and Victorian conventions being what they were, this was to cause him incalculable, if unconscious, difficulties.” The author further explores the possibility of “those sublimated passions” in a 2001 expansion of the book, inevitably titled The Full Monty.

Orde Wingate — another eccentric, pious and obsessive British officer in Palestine — had the same policy of collecting enemy bodies: “I have little faith in claims not so supported.”

“Since it was considered that I might be a target for Jewish attack,” Monty wrote in his memoirs, “a policeman was posted outside my flat at 7 Westminster Gardens.”

Fascinating and deft, as usual.

The war in North Africa is told in great detail in Martin Kitchen's "Rommel's War"