If I forget thee, Guiana

On the eve of the Holocaust, Britain shut the gates to the Holy Land and proposed a Jewish homeland in South America

In early 1939 the Neville Chamberlain government was laying the groundwork for a White Paper that would slash Jewish immigration to Mandate Palestine in a bid to quell a three-year Arab revolt that had left hundreds of Jews and British servicemen dead.

Britain’s colonial secretary — 36-year-old Malcolm MacDonald — hoped to soften the blow by offering the Jews a patch of land elsewhere in the Empire.1 The question was where.

A year earlier, U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had convened a 31-nation conference in the French resort of Évian to discuss the plight of persecuted minorities in Hitler’s Reich. The summit came to naught — of all the participating countries, only the Dominican Republic, run by a military regime keen to “whiten” its island, was ready to admit Jews as farmworkers.

Other solutions would need to be found.

Admitting Jews to Britain was scarcely considered. As revealed in Cabinet transcripts at the National Archives in London, Home Secretary Samuel Hoare warned that “while he was anxious to do his best, there was a good deal of feeling growing up in this country — a feeling which was reflected in Parliament — against the admission of Jews.”

Chamberlain’s ministers initially considered Kenya, then Northern Rhodesia (Zambia of today), but white settlers in both colonies adamantly objected.

A few months after Évian, the state-sponsored riots known as Kristallnacht brought the full predicament of Germany’s Jews — and more broadly, Europe’s — into stark relief. Five days after the pogrom Chamberlain received a Jewish delegation including Lord Herbert Samuel, Palestine’s first high commissioner, and the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann.

By this point, the archives reveal, his government had settled on a Crown colony even further afield from Zion than the savannas of Africa.

“As regards the question of mass settlement in some part of the Empire,” he told them, “the Prime Minister thought that the only possible territory might be British Guiana.”2

The 20th Century had already seen several creative ideas for a new Zion.

In 1903, an earlier Chamberlain — Neville’s father Joseph, then colonial secretary — proposed to Theodor Herzl that the Jews make their national home in British East Africa (known as the Uganda Scheme, the land was actually in Kenya).

Herzl had just traveled to Kishinev, the scene of a gruesome pogrom months earlier, and ultimately came around to the Uganda idea as a nachtasyl (“night asylum”) until conditions were ripe for a Jewish exodus to the Land of Israel. A raucous debate ensued — the Zionist Congress that year approved exploring the Uganda Scheme, only to reverse the decision two years later (resistance to the plan was led by a young Weizmann, later Israel’s first president.)

Just a few years before the Guiana proposal, authorities in Moscow turned the village of Birobidzhan — in Russia’s Far East, bordering China — into the capital of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast. Birobidzhan was intended to help solve the “Jewish question” through the cultivation of a Soviet-approved secular, socialist Jewish culture. Its language was to be not Hebrew but Yiddish; religion was strictly verboten.

At its peak, perhaps 46,000 Jews lived in Birobidzhan, about a quarter of the population. Today fewer than 1,000 remain, but the Jewish Autonomous Oblast survives. It is one of only two officially Jewish jurisdictions in the world (the other is Israel), and the only one where Yiddish is a recognized language. A large menorah dominates the entry to Birobidzhan station on the Trans-Siberian Railway.

At the same time that the British contemplated settling Jews in South America, Roosevelt’s private secretary drafted a plan to send them to Alaska (FDR, for his part, favored Angola). The so-called Jewish Desk of Nazi Germany’s Foreign Office schemed to dispatch tens of thousands to Madagascar.

The Dutch were the first Europeans to settle the stretch of South America’s northern coast that they called the “Guianas.” The British seized the area’s western portion, today’s independent republic of Guyana, in the early 19th Century. A tiny white minority ruled from the capital Georgetown (then as now, 90 percent of the populace were clustered along the coast) over a majority descended from indentured servants from India and African slaves.

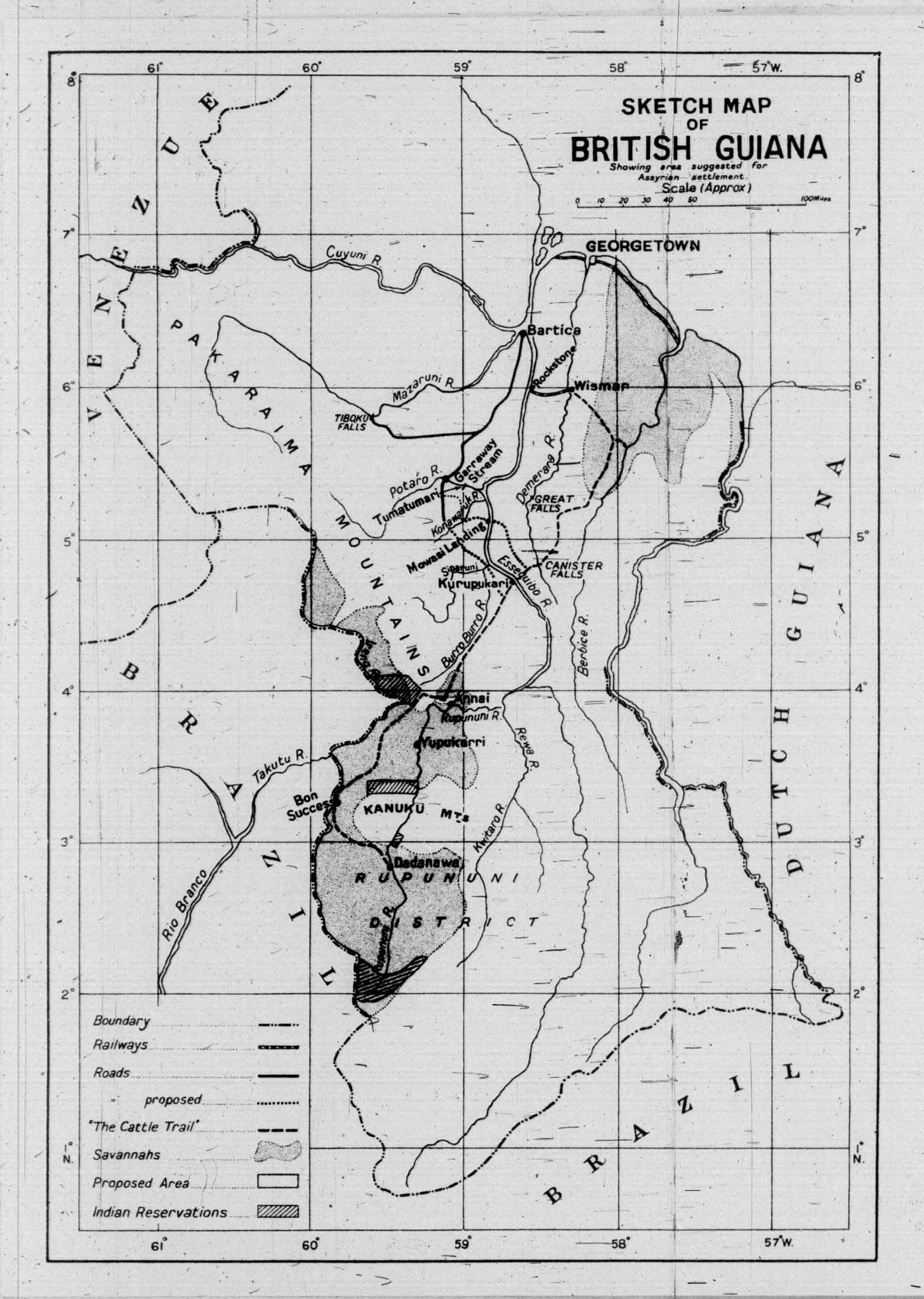

The interior presented inhospitable stretches of forests, savannas and mountains which, then as now, were either unpopulated or sparsely inhabited by indigenous tribes. And it is there, amid the Kanuku mountains and Rupununi river of the country’s southwest, that a newly formed commission explored the possibility of sending thousands of European Jews.

The British Guiana commission was a mixed British-American delegation tasked with reporting to the President’s Advisory Committee on Political Refugees that Roosevelt had formed after Évian. Chaired by Edward Ernst, an American public-health specialist, it included experts in agriculture and colonial administration and one member — the agronomist Joseph Rosen — representing the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee.

The commissioners disembarked at Georgetown in mid-February 1939 and over the next two months surveyed some 40,000 square miles by land and air. They evaluated soil quality, drainage, water availability, and vulnerability to malaria and yellow fever. They met with British officials and planters — some profoundly skeptical, others cautiously optimistic.

A spirited debate played out in the local press.

“The affairs of British Guiana must indeed be in desperate straits when the immigration of Jews is not only tolerated but in some cases actually desired,” wrote one Guyanese anonymously to the Georgetown Daily Chronicle. “While their plight is both pitiable and desperate I do not see the necessity for making British Guiana the dumping ground for them.”

He continued:

While there is no gainsaying the fact that Jews are gifted in Economics and Commerce, it is usually to the detriment of the country they reside in as they have an unusual facility in amassing wealth... Would they become keen agriculturists? Can they be kept in the hinterland away from the City?

“We are expected to be burdened with the Jews, of whom other countries... are today either expelling or refusing admission,” the writer concluded. He hoped the local authorities would “keep the Jews out of British Guiana or, if this is impossible, to reduce their number to an inconsiderable minimum.”

A more sympathetic view came from Mortimer Bayley, President of the British Guiana and Trinidad Papaw [papaya] Products Company.

“Five hundred thousand Israelites given a home in British Guiana will adorn history as the most outstanding humane contribution Great Britain has ever made to civilisation,” he wrote. “Perhaps it is the Almighty’s will that British Guiana should have remained all these years without population to become a Promised Land.”

Bayley continued:

To ameliorate the sufferings of these docile but highly industrious people is a thing that every inhabitant of British Guiana should be proud of doing... My close association for upwards of thirty years with Jews has been a period of satisfaction. They have shown me every kindness and rendered me a great assistance in business, both financially and morally.

Yet even the magnanimous fruit magnate was not above a back-handed compliment toward his longtime partners in the papaya trade:

“I do not hesitate to state that some of my aggressiveness is due to the business acumen I found among them during that association.”

In late April and early May 1939 the British Cabinet agreed upon the final terms of what history would remember as the MacDonald White Paper.

Whereas just four years earlier, in 1935, some 60,000 Jews had emigrated legally to Palestine, the new policy would cap that number at 75,000 — and not over one year but spread over five. Any further Jewish immigration would hinge on Arab consent, and it was clear to all that that consent would not be forthcoming.

With war clouds gathering over Europe, Chamberlain told Cabinet members, “it was of immense importance… to have the Moslem world with us. If we must offend one side, let us offend the Jews.”

Home secretary Hoare, one of the keenest backers of Chamberlain’s appeasement policies, agreed but added that alongside the White Paper, “we should hand over a whole colony to the Jews for settlement purposes.” The “most obvious,” he said, was British Guiana.

“The view was expressed,” the Cabinet transcript said in the passive voice, “that we might even be prepared to contemplate allowing an existing British colony to become a Jewish sovereign state.”

MacDonald strongly advised that the Cabinet release the Guiana report ahead of the White Paper to help cushion its impact. Settlement in South America could start as early as October of that year, and if it proved a success, he said, London should “be prepared to make available practically the whole colony except the coastal belt.”

Chamberlain concurred. Ministers decided to publish the Guiana report on May 11, along with a statement “emphasizing its large possibilities." The White Paper would follow exactly a week later.

Few copies of the report survive. The National Library of Israel has one; a rare books dealer in New York is selling another for $680.

Over 76 pages (and 100 more of appendices) the commissioners acknowledged the obvious: The land was swampy, malaria was endemic, and large-scale development would require massive infrastructure investment.

Still, they tried to strike a hopeful note.

“The often repeated statement that Guiana is a ‘pesthole’ with a tropical climate unfit for human habitation is definitely based on a misapprehension or deliberate misrepresentation,” they insisted with noticeable defensiveness.

“The climate is by no means unbearable,” they added encouragingly.

On relations with the indigenous population, they were persuaded there was little to worry about:

As to the Indians themselves, there is good reason to believe they will welcome the coming of white settlers... They are an intelligent and well disposed people, suspectible of a high degree of civilization… they see in the project three features highly desirable in their eyes: education, medical attention, and a market for their labor.

The report concluded that the land had potential for agricultural and even some industrial development, and that significant Jewish settlement might ultimately be feasible. They recommended an initial two-year trial of “a population of 3,000 to 5,000 carefully selected young men and women” to test whether “Europeans” could adjust to the harsh conditions of the Guianese interior. The cost of launching such an experiment was estimated at $3 million ($150 million today).

At no point were Jewish leaders asked how they viewed the prospect of moving to this remote corner of the Empire. Once the report was released, they mostly ignored it. Meeting Colonial Secretary MacDonald two days after, Weizmann refused to even utter the word Guiana (“I just brushed it aside with a sweeping gesture,” he recalled).

The White Paper, however, sparked massive protests both in the Holy Land and the Jewish diaspora (even the New York Times editorialized against it). At Jerusalem’s Zion Square (British cables erroneously called it “Zionist Square”), a Jew with a Mauser shot dead a constable named Lawrence. David Ben-Gurion, head of the Jewish Agency, told British officials they were witnessing “the beginning of Jewish resistance.”

Four months later the Second World War began. The Guiana plan was binned, and throughout the war years only a few dozen Jews were allowed to settle there. Very few would stay permanently.3

The Guiana affair is long forgotten. At the time, it was said, the Jews referred to the place as British “Gehenna” — a biblical Hebrew word roughly analogous to hell.4

The allusion to the inferno was apt. Exactly four decades earlier, in 1899, the archetypal figure of the spurned Jew of Europe was finally released after four years’ banishment and confinement, alone, on a rock off of the French-ruled eastern portion of Guiana.

His place of exile was called Devil’s Island; his name was Alfred Dreyfus.

Malcolm MacDonald was the son of Ramsay MacDonald, Britain’s first Labour prime minister and an early sympathizer with Zionism.

Chamberlain told his guests: “The grant of a tract [in Guiana] might be a possible contribution on the part of His Majesty's Government, and if made it might encourage other Governments to be more forthcoming than hitherto.”

By far the most famous Jew in Guyana’s modern history was Janet Jagan (born Janet Rosenberg in Chicago), the country’s president from 1997 to 1999. But she herself told a journalist in 2000 that “Jewishness wasn’t much of a factor” in her life.

The “Gehenna” reference comes from historian Christopher Sykes, son of the diplomat Mark Sykes of Sykes-Picot fame.

Not many welcoming arms.