Mahatma Gandhi’s Zionist ‘soulmate’

The Great Soul opposed Jewish statehood, but his ‘lifelong companion’ left his fortune to Israel and his ashes in Galilee

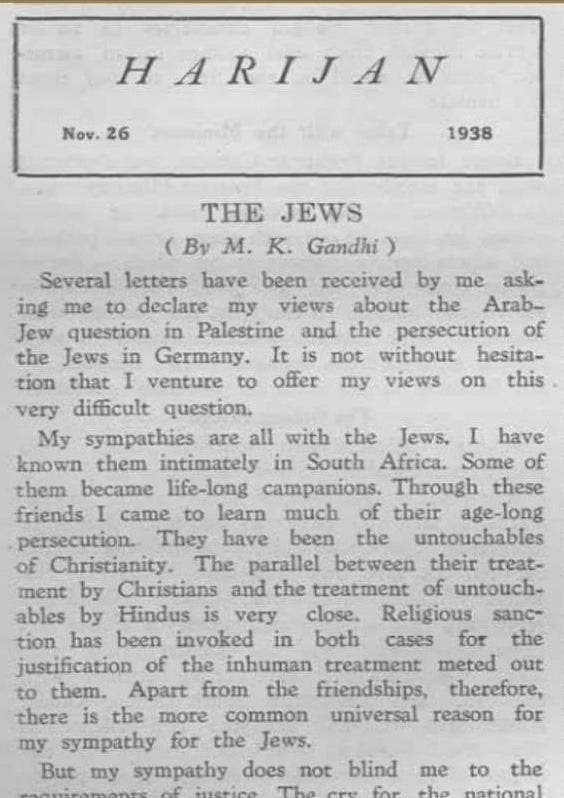

On November 11, 1938, Mohandas K. Gandhi sat down at his ashram home in Sevagram, in the heart of India, to write an essay. It was to appear in his newspaper Harijan — “children of God,” as he called the Dalit, or untouchables. It was the day after Kristallnacht.

The essay, titled simply “The Jews,” began thus:

“Several letters have been received by me asking me to declare my views about the Arab-Jew question in Palestine and the persecution of the Jews in Germany. It is not without hesitation that I venture to offer my views on this very difficult question.”

He continued:

My sympathies are all with the Jews. I have known them intimately in South Africa. Some of them became lifelong companions. Through these friends I came to learn much of their age-long persecution. They have been the untouchables of Christianity … Apart from the friendships, therefore, there is the more common universal reason for my sympathy for the Jews.

The popular memory so associates Gandhi — the icon hailed as the Mahatma, or great soul — with Indian independence that we often forget he spent two decades, from his mid-20s to mid-40s, in British-colonial South Africa. There he struggled for the rights of Indians, many of them indentured laborers, who faced a host of restrictions on where they could live, travel and work.

It was there that his spiritual and political philosophy coalesced. And while there, his milieu was predominantly Jewish.

“I have a world of friends among the Jews,” Gandhi had told a reporter a few years before writing the essay. “In South Africa I was surrounded by Jews.”

These included Henry Polak. In 1905 Gandhi employed him to edit his newspaper Indian Opinion in the commune he had built near Durban in the Natal region. And they included Sonja Schlesin, whom Gandhi hired the same year as his personal secretary, and whom he praised in his autobiography for her “character as clear as crystal and courage that would shame a warrior.”

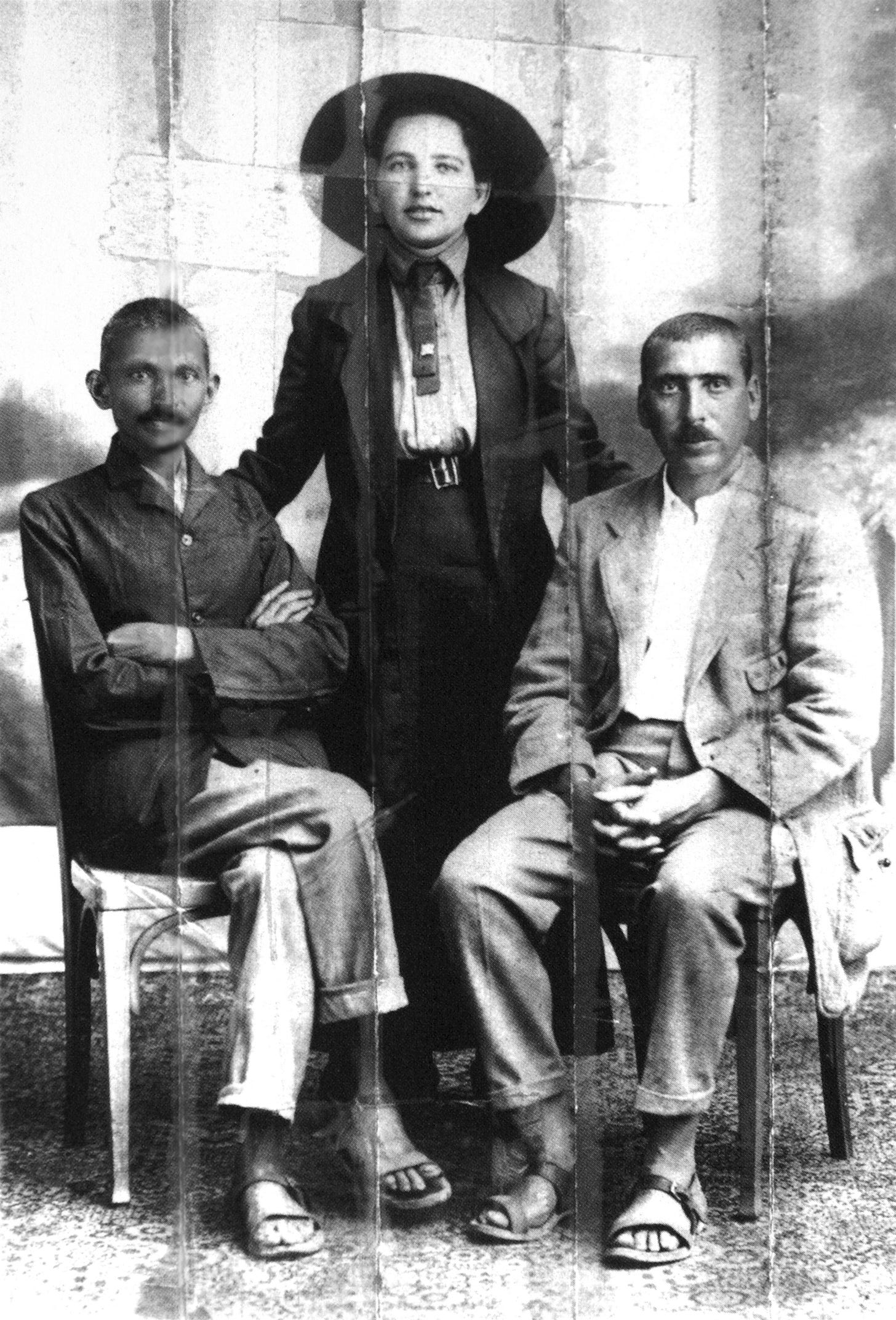

But most intimate of all was his relationship with Hermann Kallenbach. Kallenbach was born in Lithuania and raised in Germany (his father had Germanized their surname from Kalmanovich), and after immigrating to South Africa as a young man had built a successful career as an architect.

He first met Gandhi in 1903, when both were in their early 30s. From about 1907 Gandhi stayed intermittently at Kallenbach’s comfortable Johannesburg residences, but soon the wealthy developer started adopting the diminutive lawyer’s ascetic personal habits as his own.

As Gandhi recalled in that same autobiography:

When I came to know him I was startled at his love of luxury and extravagance. But at our first meeting, he asked searching questions concerning matters of religion. We incidentally talked of Gautama Buddha’s renunciation. Our acquaintance soon ripened into very close friendship, so much so that we thought alike, and he was convinced that he must carry out in his life the changes I was making in mine.

In 1908 Kallenbach built a simple two-room home called the Kraal, or barn in Afrikaans, where the two of them lived. In time it would be known as Satyagraha House, that being the Sanskrit word Gandhi adopted for his “truth force” of nonviolent resistance — to British repression of Indians in South Africa (and, decades later, in India itself). The pair lived together there for a year and a half, then another half-year in a tent on one of Kallenbach’s properties in Johannesburg’s Linksfield quarter.

They called each other Lower House and Upper House, a reference to the bicameral British parliament. Kallenbach, being the source of appropriations, would propose a budget, and Gandhi, as the frugal purse-minder, would often vote down excessive spending.

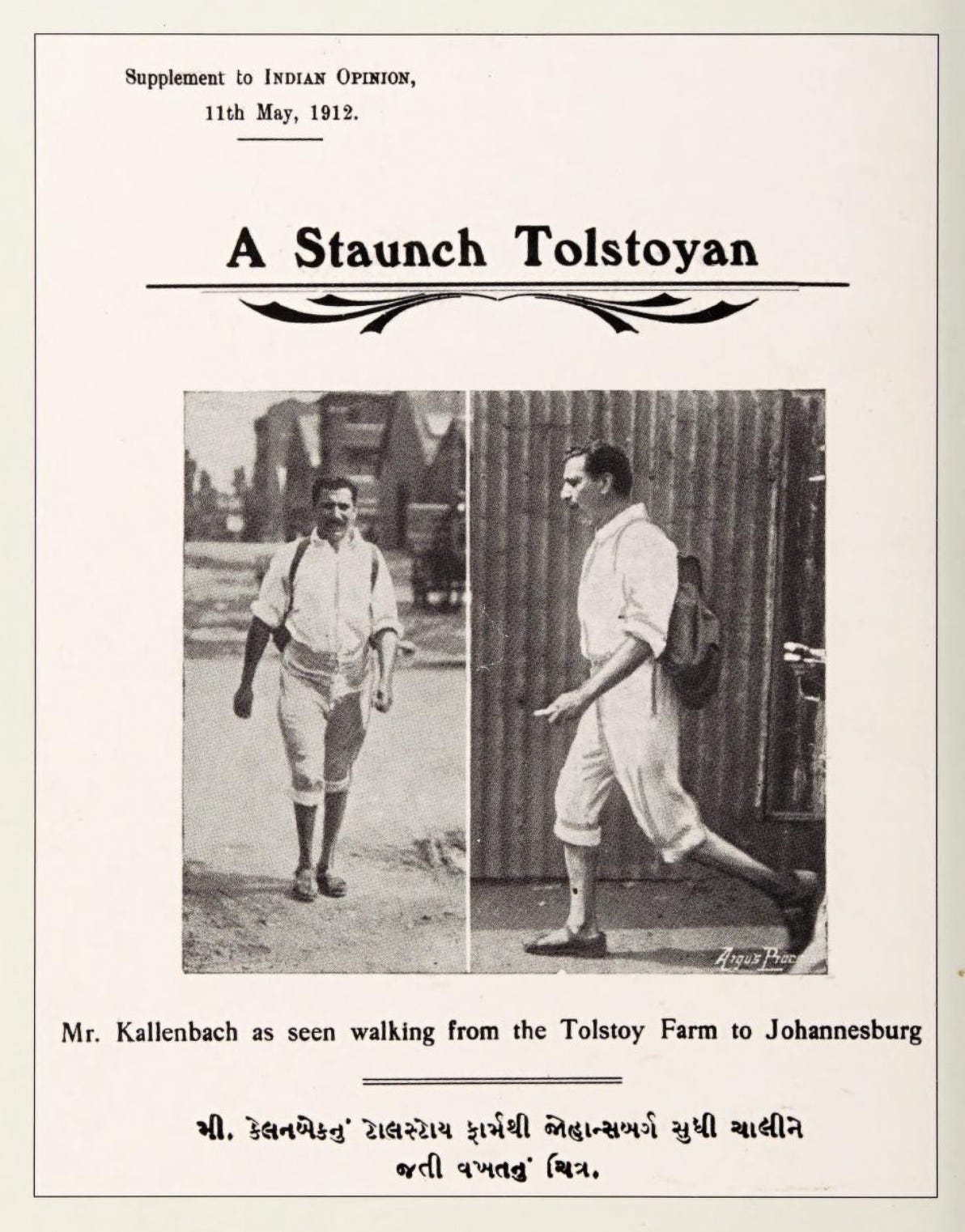

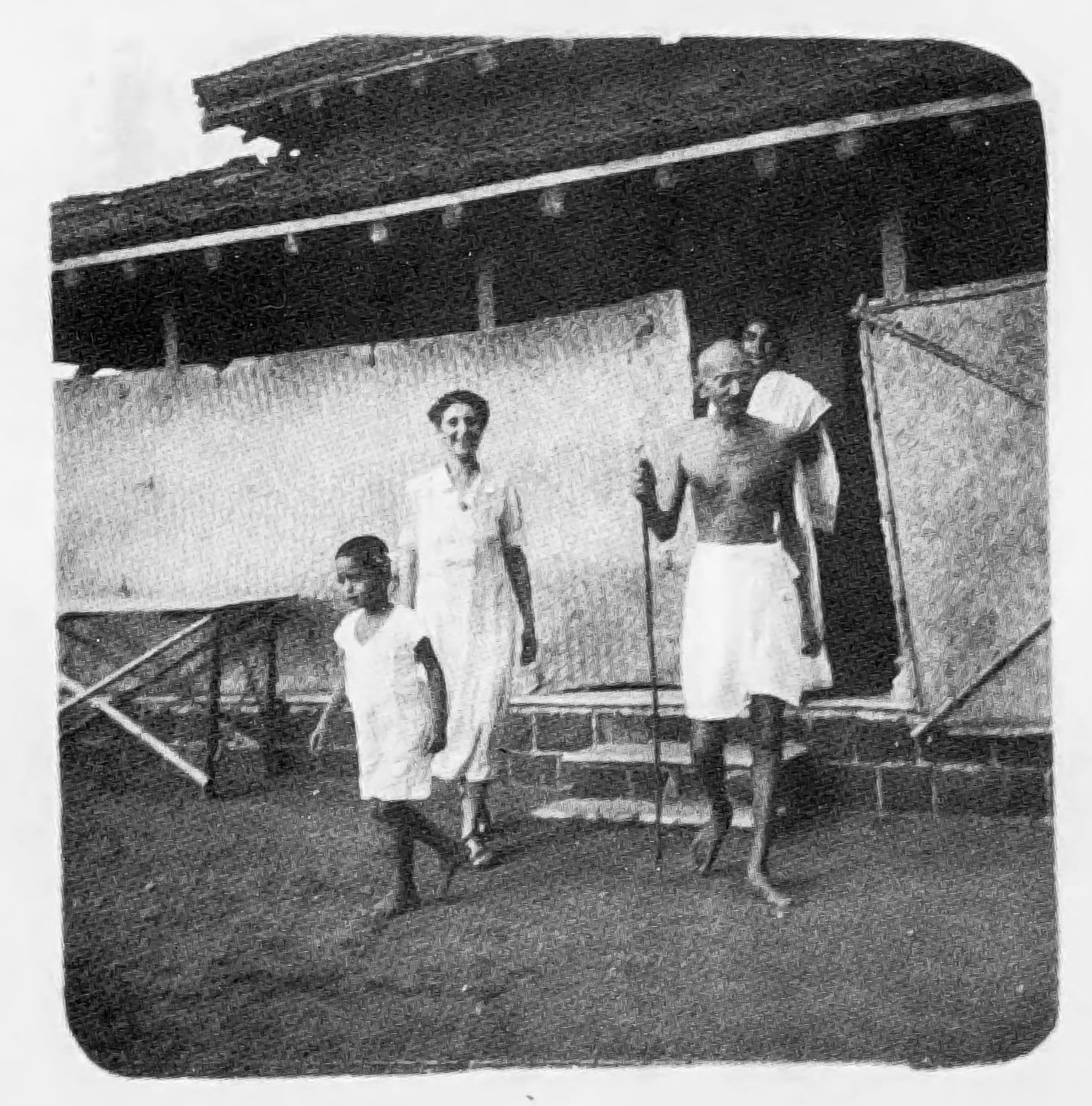

In 1910 Kallenbach bought the land southwest of the city that became Tolstoy Farm, a self-sufficient village where members kept a vegetarian diet and sustained themselves physically and spiritually. They both moved onto the farm (they even got the great Russian’s permission to use his name before he died), but were now joined by several dozen others — mostly Indian Hindus but also some Muslims.

Whenever they went to town, they would complete the 20-mile, five-hour trek through the veld of what would later be the apartheid-era township of Soweto. A 1912 photo from Indian Opinion, captioned in English and Gujarati, depicts Kallenbach as a “Staunch Tolstoyan,” walking ahead with an upright gait.1

“My faith and courage were at their highest in Tolstoy Farm,” Gandhi later recalled wistfully.

The following year Kallenbach played a key role in organizing the Great March of thousands of Indians from Natal to neighboring Transvaal in defiance of laws limiting their movement. He and Gandhi each served several months in prison.

Kallenbach was released from prison first. Once Gandhi was freed, Kallenbach surprised him by picking him up in an automobile — only to find his friend silent and sullen on the ride home. After a year of never using the vehicle, the architect reluctantly sold it (years later Gandhi threw an expensive set of binoculars into the sea; when Kallenbach got another pair as a gift they met the same fate).

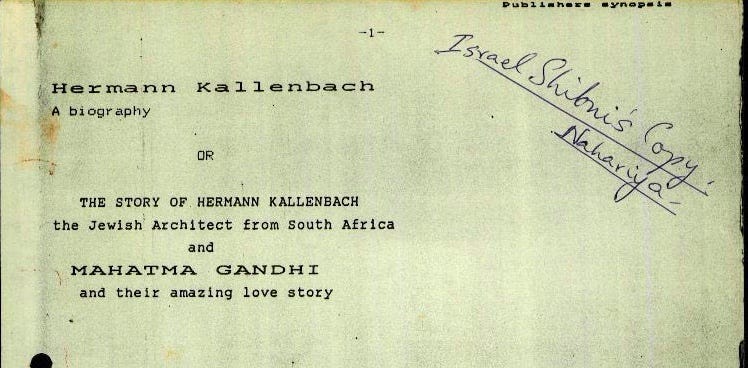

A 2011 book by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Joseph Lelyveld prompted an international stir by describing the pair as no less than a “couple” (Was Gandhi Gay?, asked the Wall Street Journal at the time). Gandhi’s native Gujarat state even banned the book. Less well-publicized was the 1997 book co-authored by Kallenbach’s Israeli grand-niece on their extraordinary, mostly-forgotten relationship. Its original subtitle, per the Kallenbach family archive in Haifa, referred to “their amazing love story.”

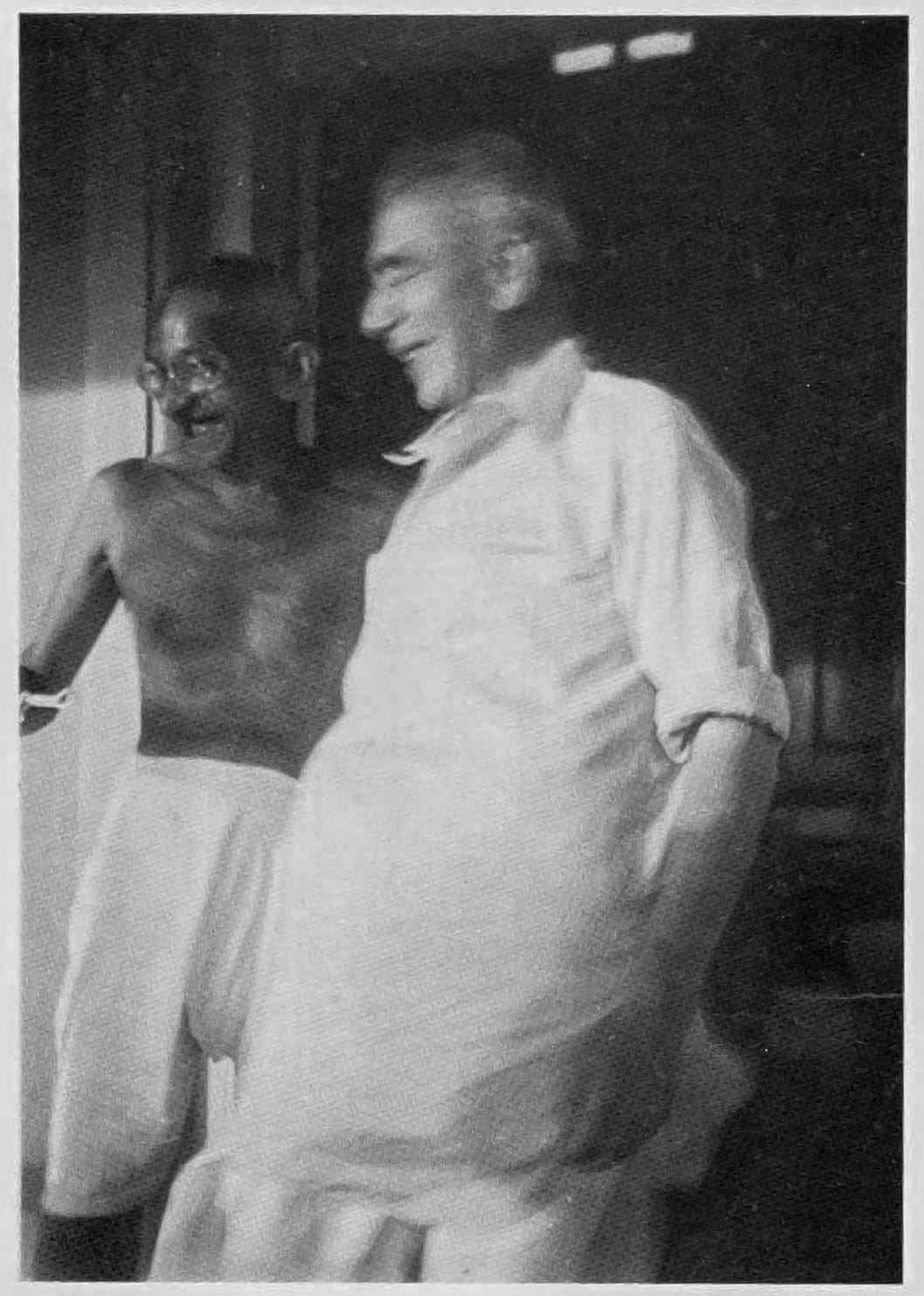

For Gandhi’s part, as documented by the Israeli scholar Shimon Lev, he referred to Kallenbach as his “soulmate” and their correspondence as “love letters.”

Lev believes their bond had a romantic element, but not a consummated sexual one. Gandhi took an oath of celibacy in 1906 and kept it for much of his life, deeming sexual abstinence necessary for rising above an “animal life” toward spiritual growth and public service. Kallenbach took the same oath the year after.

“Nonetheless, it appears that their relationship was homo-erotic in nature,” Lev writes in his book Soulmates: The Story of Mahatma Gandhi and Hermann Kallenbach, published in India in 2012.

“I believe that the sexual energy that arose from this closeness was channeled towards personal, spiritual, and moral growth,” he concludes. “We will never know precisely to what extent sexuality defined the nature of Gandhi and Kallenbach’s relationship. Even so, it is impossible to ignore.”2

“We will never know precisely to what extent sexuality defined the nature of Gandhi and Kallenbach’s relationship,” writes historian Shimon Lev

Whatever that relationship, it was cut short by force majeure. In mid-July 1914 the pair boarded a ship to India by way of Britain. In those days the journey to London took three to four weeks. By the time they disembarked, the Great War was in full flame.

Kallenbach was a German citizen and German army veteran, and the British imprisoned him on the Isle of Man. Gandhi was forced to continue to India on his own. Kallenbach was only released in 1917, in a prisoner exchange that sent him to Berlin. For the next three years there was apparently no correspondence between the two. The precise reasons remain obscure.

Kallenbach returned to South Africa, “leading his old life and doing brisk business as an architect,” as Gandhi wrote in his autobiography with ill-concealed scorn. He built high-rise offices, theaters, synagogues and churches, and developed the Linksfield area into an affluent neighborhood that still boasts the swanky, decidedly un-Gandhian Kallenbach Drive. Still, he never quite cut the cord with his famous companion — even as he grew wealthier, he spent relatively little and maintained a certain asceticism in his habits.

Had he gone to India, he likely would have become manager of Gandhi’s ashrams. Instead, as the Mahatma attracted international attention in the land of his birth, his “lifelong companion” remained and remains mostly unknown in the three countries where he ought to be most remembered: in South Africa, in India and in Israel.

More than two decades would pass before the pair would reunite. It happened in 1937, when Kallenbach made his first voyage to Mandate Palestine, followed by his first to India.

Both visits came at the initiative of the Zionist leader Moshe Shertok (later, as Moshe Sharett, Israel’s first foreign minister). In July 1936, two months into the Great Arab Revolt, he sent Kallenbach a five-page letter.

In the Jewish people “returning to its home in Asia,” Shertok wrote, the goodwill of the “great Asiatic civilizations” would be paramount. Kallenbach was “in a unique position to help Zionism” in a field where its resources were “so meager as to be practically non-existent.”

Kallenbach answered the call enthusiastically: “I am coming.”

He had shown his first interest in Zionism as early as 1913, and first donated money to the cause in the mid-20s. By the mid-30s, increasingly horrified by Nazi depredations, he was a fully committed Zionist, often going by the name Chaim — life — as his personal form of nonviolent protest.

In spring 1937 he arrived in Palestine. The visit was short but impactful — he was particularly stirred by the Galilee kibbutzim.

“There is intense and joyful work taking place everywhere,” he wrote his brother Simon in Germany. “This is a Rejuvenation of our People.”

Palestine, the land of my fore-bears, with its strenuous endeavours and many experiments of my people, has thrilled me. Great difficulties are facing us there, and we shall succeed only if the moral values are greater in us than the material ones.

From Egypt, he continued to India. At 4:30 AM on May 20, 1937, he arrived at Tithal, the village near Mumbai where Gandhi was staying. The Mahatma was deep in morning prayers with his disciples. They had not seen each other for 23 years.

“A father and brethren could not bestow more love and kindness on me than I am receiving daily by him,” Kallenbach wrote Shertok. “I feel at home here.”

They spent three weeks there, then another six at Gandhi’s new ashram at Sevagram. Through their long walks and talks, Kallenbach tried to bring his old friend around to a greater appreciation of Zionism. He found only limited success.

Lev notes a gap between Gandhi’s public objection to political Zionism and his support for Kallenbach’s “private Zionism.” He continued to insist that Jewish dreams for Palestine could only be realized with Arab goodwill, and refused any political program that circumvented it — particularly one that relied on coercion, political or military, from the imperial authorities of the British Mandate. But as to Kallenbach’s growing desire to settle there as a farmer, the Mahatma was fully onboard.

Gandhi even expressed interest in leading a secret Jewish-Arab mediation effort — alongside Kallenbach and the Anglican priest C.F. Andrews — but for various reasons it never had a chance.

For one thing, he had called for Zionist leaders to make a statement abandoning their reliance on Britain and depending purely on Arab goodwill. Amid the bloodletting of the Arab revolt, this was further than those leaders would go.

Second, Muhammad Ali Jinnah was becoming an ever-louder voice for Muslim self-determination in — and separation from — India. Gandhi knew that publicly backing any Jewish claims in Palestine would have been a gift to his rising Muslim rival. When Britain first proposed partitioning Palestine in 1937, Gandhi was studiously quiet, lest India’s Muslims demand the same (though that’s exactly what happened a decade later, with Jinnah at the helm of the new state of Pakistan).

Third, a pillar of the plan — Kallenbach — was tied up with business in South Africa and desperately trying to get his family out of Germany (he ultimately got his brother on the very last ship out of the Reich).

He sent his niece Hanna Lazar to India instead.

Gandhi adopted her as a daughter, and she would forever recall her time at the ashram as “the most important event in my small life.”

But she soon got severely ill and made her way home to Johannesburg. Ghandi’s intervention in the Middle East conflict — a tantalizing piece of what-if history — never happened.

It was then that Gandhi decided to write the Harijan article. It would prove controversial ever since — both for what he wrote about Zionism and, as it happens, about Nazism.

My sympathies are all with the Jews … But my sympathy does not blind me to the requirements of justice. The cry for the national home for the Jews does not make much appeal to me.

Palestine belongs to the Arabs in the same sense that England belongs to the English or France to the French. It is wrong and inhuman to impose the Jews on the Arabs … The Palestine of the Biblical conception is not a geographical tract. It is in their hearts … They should seek to convert the Arab heart.

“I am not defending the Arab excesses. I wish they had chosen the way of non-violence,” he wrote. And he reiterated his call for the Jews to do just that:

Let the Jews who claim to be the chosen race prove their title by choosing the way of non-violence for vindicating their position on earth. Every country is their home including Palestine not by aggression but by loving service.3

For Gandhi, satyagraha was an invincible force even in the face of the Nazi menace:

The calculated violence of Hitler may even result in a general massacre of the Jews … But if the Jewish mind could be prepared for voluntary suffering, even the massacre I have imagined could be turned into a day of thanksgiving and joy that Jehovah had wrought deliverance of the race even at the hands of the tyrant. For to the godfearing, death has no terror. It is a joyful sleep to be followed by a waking that would be all the more refreshing for the long sleep.

The last quote appears in a fascinating piece by Zack Rothbart last month in The Times of Israel. Rothbart explores the limits and contradictions of Gandhi’s vision of non-violence — thereby sparing me the need to do so (I’m well above my intended word count anyway).

He notes that in “a vacuum, these statements may make Gandhi out to be something between a blindly naive buffoon and a blatant Nazi sympathizer” (while hastening to add that he considers him neither).

And he interviews the Oxford historian Faisal Devji, who acknowledges: “This was difficult and perhaps grotesque advice to give, but Gandhi did so to all those who came to him.”4

The same day that Gandhi wrote “The Jews,” he wrote Kallenbach admitting a certain unease: “You will have seen my article on the Jews. I have made a plunge into unknown waters.”

The article drew bitter criticism even from admirers, including leading intellectuals from the progressive fringes of Zionism. Martin Buber, who had fled Nazi Germany for Jerusalem just months before, and Judah Leib Magnes, the San Francisco-born president of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, released a joint booklet in Hebrew denouncing the essay. In it Ghandi had equated German persecution of Jews with that of Indians in South Africa — a comparison Buber dubbed “tragi-comic.”

“You will have seen my article on the Jews. I have made a plunge into unknown waters.”

It is unclear why he had not consulted Kallenbach, who must have found the article deeply distressing. No record remains of his response.

We do know that the architect decided to travel to India immediately, and penned a letter to Jawaharlal Nehru — Gandhi’s younger acolyte and later India’s first premier — begging for Indian visas for German Jews. “Please help us,” he scrawled at the bottom in bold print.

In London, the Neville Chamberlain government was planning a Palestine summit expected to significantly roll back Jewish immigration (the result would be the famous White Paper of May 1939).

As Lev reveals in his book, Kallenbach cabled Gandhi: “Suggest yourself [and] Nehru appeal this conference not to debar my people from their only remaining permanent refuge [and] home. Leaving Durban 1 January. Love, Lower House.”

Three weeks later he arrived in Mumbai, met Gandhi and traveled 600 miles with him to the ashram. Soon after, Kallenbach contracted malaria and was confined to bed for most of his stay. It would be their last time together. On the last day of March 1939 he returned home to South Africa.

“Kallenbach left today; he was fretting,” Gandhi wrote. “The house is empty.”

Months later, in late August, Kallenbach wrote him a letter, possibly the last they ever exchanged.

“The joy of life is mostly absent,” he wrote. “My people’s fate is paralysing me. I thank you deeply for inviting me to India; I may still come, as you know my happiest time in my uneventful and hardly useful existence I have spent in your company.”

Five days later the Second World War began.

Kallenbach did not live long enough to learn the extent of the cataclysm, nor to confront Gandhi over his controversial comments before the war and his near-silence on the Holocaust after.

Again, Lev:

What is perhaps the strangest of all is that when the extent of the Nazi genocide was revealed to the world after the War, Gandhi kept silent. Gandhi may have chosen to avoid the subject because his misjudgement was so obvious. In addition, he no longer felt a personal obligation to Kallenbach.

One of his only recorded remarks on the topic was made in 1946, to one of his biographers. It showed that even they he had not budged from his position, however much it saddened and enraged Kallenbach, Polak and many of his other Jewish friends.

Again, from Rothbart’s piece:

It is the greatest crime of our time. But the Jews should have offered themselves to the butcher’s knife. They should have thrown themselves into the sea from the cliffs … It would have aroused the world and the people of Germany … As it is they succumbed anyway in their millions.

Hermann Kallenach died on March 22, 1945, fatally weakened by the lingering effects of the malaria he had contracted in India. He had never married. His will, inspired by Indian custom, stipulated that his body be cremated, causing something of a scandal among the Jews of Johannesburg. In segregated South Africa, the Indians who came to pay respects had to stand outside the crematorium door.

Gandhi followed him out of this world on January 30, 1948, felled by an assassin’s bullet. Neither lived to see the birth, in May of that year, of the Jewish state of Israel.

Kallenbach wrote several wills in his life. In the first three he left all of his fortune to Gandhi. In the next two, he split it between Gandhi, his family and the Zionist institutions. In his final will, he left everything to Keren Hayesod (United Israel Appeal) for the creation of agricultural villages. His library of some 7,000 books went to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

It appears, paradoxically enough, that Gandhi had something to do with it. Hearing that his friend intended to donate his money to the cause of Indian independence, he advised him instead to help “the Jews who are most deserving.”5 Kallenbach appears to have concluded that that meant the Jews living in, or destined to live in, the Promised Land.

Only some of Gandhi’s letters from Kallenbach survive; the rest were destroyed at the latter’s request. (After Gandhi’s death, his secretary destroyed all of his papers on Palestine, deepening the archival gap.) Most of the letters in the opposite direction — from Gandhi to Kallenbach — ended up in the possession of the architect’s niece Hanna, who in the early 1950s moved to Israel. Later, in the 80s, the Indian government bought one trove of the correspondence from the family.

The rest stayed with Hanna’s daughter Isa, who kept them in a tiny room in her Haifa apartment. In 2012, after she died, her family sold the remaining correspondence to Sotheby’s. The Indian government bought those too, for over $1 million, lest they fall into private hands.

In 2015, a poignant statue of Gandhi and Kallenbach was unveiled on a riverbank near the latter’s Baltic birthplace. The Lithuanian prime minister presided, with descendants of both men in attendance.

Most of the funds came from Yusuf Hamied, a Lithuania-born, Mumbai-raised pharma tycoon who is the son of a Muslim father and Jewish mother. To honor his mother, whose parents perished in the Holocaust, Hamied commissioned a concert at the site conducted by Zubin Mehta, a childhood friend from Mumbai and the decades-long maestro of the Israel Philharmonic.

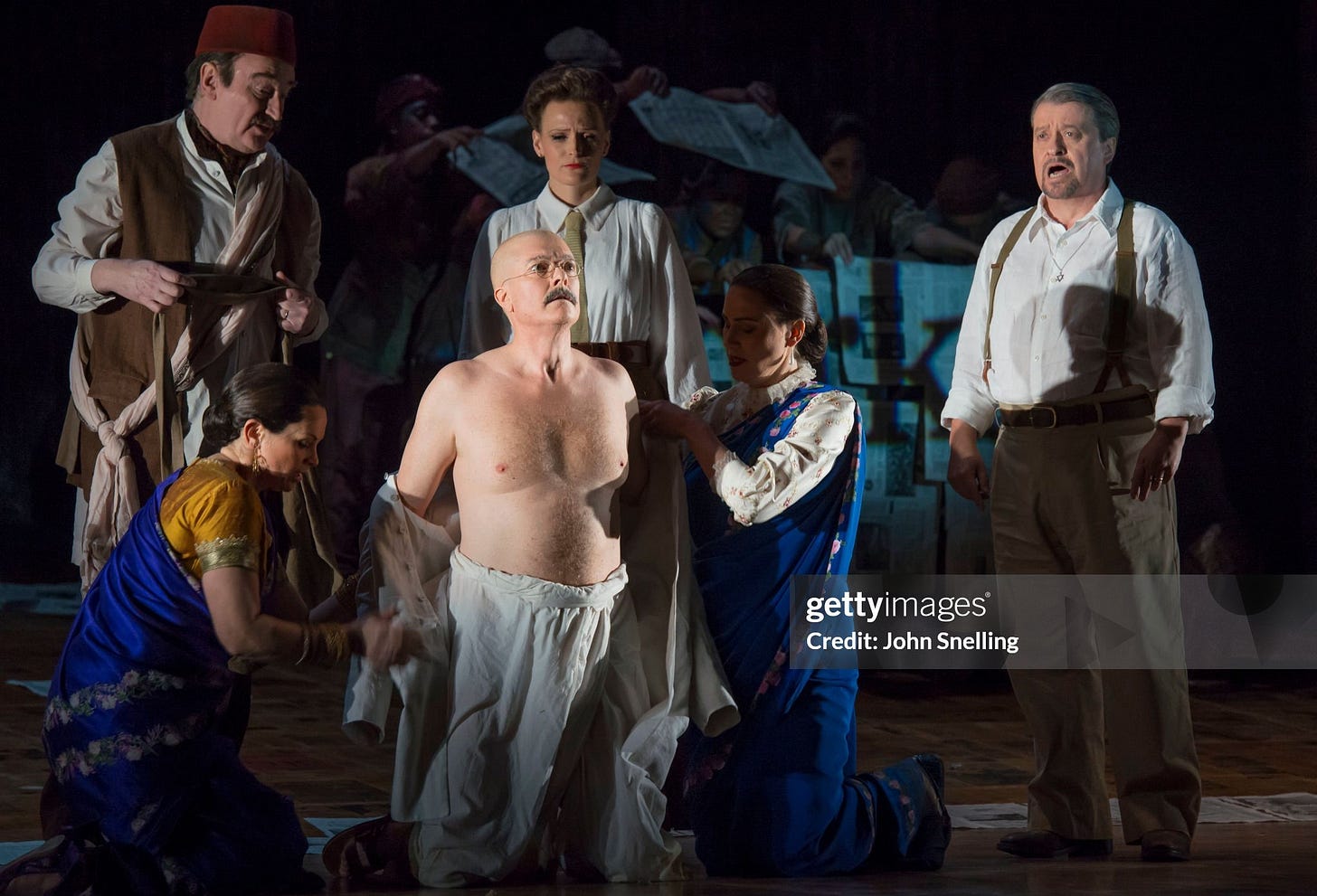

And recent years have seen growing interest in Philip Glass’s 1980 opera Satyagraha, including landmark productions by the English National Opera and the Met. On stage as in life, Kallenbach (at right below, with Star of David pendant) plays one of Gandhi’s key supporting roles.

Degania, in the Galilee, is the oldest kibbutz in the Land of Israel, created in 1910 — the year Kallenbach and Gandhi founded Tolstoy Farm outside Johannesburg. A few years later, a 63-year-old named A.D. Gordon settled there and dedicated his last years to a life of “bread-labor” — the Tolstoyan creed of earning one’s sustenance from the soil.

In the kibbutz cemetery, near Gordon’s tomb, is another one, easy to miss, and written entirely in Hebrew.

Kallenbach’s will had asked that his ashes go to Degania, which he had visited on his 1937 visit. There, it seems, he felt the various streams of his spirit converge, just as the Jordan river meets the Sea of Galilee a short walk away. In 1952, when his niece Hanna moved to Israel, she brought his ashes with her and laid them there in a small ceremony.6

“Chaim (Hermann) Kallenbach of Johannesburg,” says the inscription, above the Hebrew and Gregorian dates of his birth and death.

The only other words are these, inspired by Psalm 15:

“Shocher tov. Doresh tzedek. Holech tamim.”

Seeks the good. Demands justice. Walks upright.

In Gandhi and the Middle East, historian Simone Panter-Brick writes of Kallenbach: “athletic, tireless walker, an accomplished tennis player, a champion ice-skater, he was as upright morally as he was physically.”

The most quoted letter from Gandhi hinting at a romantic relationship is from 1909: “Your portrait (the only one) stands on the mantelpiece in my room. The mantelpiece is opposite the bed … Therefore, even if I wanted to dismiss you from my thoughts, I could not do it … how completely you have taken possession of my body. This is slavery with a vengeance.”

The historian P.R. Kumaraswamy wrote an entire book on Gandhi and Zionism: Squaring the Circle: Mahatma Gandhi and the Jewish National Home (Routledge, 2021). He depicts the Harijan article as the apex of Gandhi’s pro-Arab feeling, which he argues swung in his final decade toward the Jews. Panter-Brick’s work reaches similar conclusions.

In 2019 Rothbart revealed a Rosh Hashana greeting, held by the Israel National Library, that Gandhi sent to the Indian Zionist A.E. Shohet on the first day of World War II: “You have my good wishes for your new year. How I wish the new year may mean an era of peace for your afflicted people.” Rothbart also generously reviewed my book last year for Haaretz.

Lev’s book quotes an Austrian-Jewish refugee in South Africa to the same effect: that Gandhi said that just as he was working for his own Indian people, Kallenbach should “save his own people, that is, the Jews.”

Interesting that Kallenbach arrived just before Peel was published. I wonder what the talk was like on the street, where he was.

I remember hearing that Gandhi used to have naked women sitting in his lap, as a way of proving his self control. No clue if that is true - but when I heard it I made space in my head for the probability of his being gay. Now that I know that thoughts of some guy “took possession of his whole body”, I’ve made even more space. Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

So Sharett reached out to Kallenbach? How did he know of him? Was Kallenbach a famous architect?

Great piece.

Thanks for this fascinating piece! I find Gandhi’s views to be hopelessly naive and even sinister in some ways, with his reaction to the Holocaust being the ultimate failed test of his moral authority. Still, it seems that he did at least have an admiration for his Jewish friends that is belied by his out of context but very disturbing comments about Jews in the Holocaust.