My grandfather’s diary of Romania’s Holocaust

Dr. Arthur Kessler’s concentration camp diary of Transnistria, the ‘forgotten cemetery,’ is released

Welcome to my first Substack post!

I don’t intend to post very much about the Holocaust (some 20,000 books have already covered that terrain, by one count), but the publication of my late grandfather’s concentration camp memoir seems as momentous an occasion as any to launch this channel. Please consider subscribing below, and please share with friends.

Update (October 31): For Part II of this post, “The poison peas,” click here.

Romania was Hitler’s staunchest ally for most of World War II, contributing more troops to the Axis war machine than all other armies combined and responsible for the murder of more Jews — between 280,000 and 380,000 — than any country after Nazi Germany. Not for nothing do historians call the genocide that unfolded there the “forgotten Holocaust.”

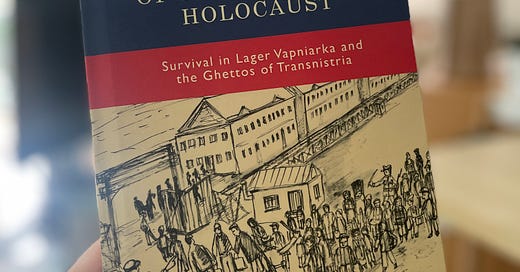

Last month saw the publication of the wartime diary of Dr. Arthur Kessler, my late grandfather. A Doctor’s Memoir of the Romanian Holocaust is based on notes that Dr. Kessler wrote while imprisoned in Vapniarka, a concentration camp in Transnistria — a region that Romania seized, with German help, in 1941 from Soviet Ukraine. As Romania’s is the forgotten Holocaust, Transnistria is its “forgotten cemetery.”

Vapniarka was a particularly grim locus of cruelty, where prisoners were fed horse fodder that permanently paralyzed those whom it didn’t kill first. It was Dr. Kessler who identified the cause of the paralysis and, at tremendous risk, helped lead a hunger strike that persuaded the camp commanders to change inmates’ rations.

“Gripping, essential, important,” tweeted historian Simon Sebag Montefiore, author of Stalin and Jerusalem: The Biography.

Radu Ioanid – the world’s foremost historian on the Romanian Holocaust, who happens to be Bucharest’s ambassador to Israel — called it an “extremely important book.”1

In a perfect coincidence, it was published by the University of Rochester (my hometown) as part of its Rochester Studies in East and Central Europe, edited by the historian Timothy Snyder (Bloodlands, On Tyranny).

But I should slow down.

Romania is, to paraphrase Neville Chamberlain on Czechoslovakia, a faraway country that most of us know nothing about.

First, some context.

Romania is Europe’s twelfth-largest country, roughly the size of the United Kingdom. Perched where the Balkans meet Eastern Europe, it borders Ukraine, Hungary and Moldova to the north and Serbia and Bulgaria to the south. Most of its 20 million people speak the only major Romance language east of the Italian peninsula (albeit with strong Slavic influence), a result of the ancient Romans’ lust for gold in the land they called Dacia.

That imperial inheritance remains in the Romanian Orthodox faith, a Byzantine rite church that is core to many Romanians’ self-conception. Centuries of war against (and subjugation by) the Islamic Ottoman Empire helped cement Romania’s self-image as guardian of the true cross.

The late 19th Century brought independence from the Ottomans and the start of a royal line. Romania joined the Allies midway through the Great War, a sage decision that allowed it to double in size, taking Transylvania from Hungary, Bessarabia (roughly today’s Moldova) from Russia, and — critically for our story — Bukovina from the dismantled Austrian empire.

The Allies had conditioned that expansion on Romania signing a treaty protecting its newly absorbed linguistic and religious minorities: Hungarians, Ukrainians, and of course Jews. For decades after, that treaty — codified in Romania’s 1923 Constitution — would be a sore spot for Romania’s ultra-nationalists and arch-traditionalists.

Through the 1920s and 30s, groups like the Orthodox-fascist Iron Guard (also known as the Legion of the Archangel Michael) waged anti-Semitic campaigns in the name of Romanianization — which so often meant de-Judaizaton — of the country’s culture, religious life and economy. The specter of “Jewish Bolshevism” loomed particularly large in their fever dreams. The constellation of anti-Semitic movements in interwar Romania, several of them sporting swastikas, is vast (see here, here, here and here, for starters).

“Antisemitic rhetoric was used extensively by all the major political parties in interwar Romania,” writes Grant Harward, a U.S. Army historian, in his recent book Romania’s Holy War: Soldiers, Motivation, and the Holocaust.2

King Carol II was a conservative with ambivalent views on Jews. He did not typically spearhead anti-Jewish actions but on several occasions allied with some of the worst Jew-baiters to exploit existing hostility, shore up support and counter the popularity of the Iron Guard.3

In 1938, increasingly threatened by the Guard, he declared a royal dictatorship, suspending the constitution and enacting one-party rule. With the start of World War II the next year he declared neutrality, but a string of subsequent German victories prompted him to lean steadily closer to Hitler.

And yet in June 1940 the Soviets invaded Romania to regain their lost province of Bessarabia, and for good measure, seized the northern half of neighboring Bukovina too.4

The king scrambled to appease the enraged masses by (what else?) anti-Semitic legislation. The August 1940 “Jewish Statute” was Romania’s version of the Nuremburg Laws, drawing a bright line between Romanians of “blood” and of those of citizenship, and banning intermarriage between the two. The gambit was insufficient, and amid the humiliation Carol was forced to abdicate in favor of his teenage son.

But Carol’s opportunistic anti-Jewish measures paled in comparison with what was to come. From his abdication, real power lay with the new prime minister: Ion Antonescu, a profoundly Judeophobic army general and an ally of the fascist Iron Guard.

Thus begins the tragic, overlooked and undertold tale of the Romanian Holocaust.

Bukovina’s capital was Czernowitz, an outpost of Hapsburg architecture and kultur bearing the moniker (along with several other claimants) of “Little Vienna.” It is there that Arthur Kessler, born 1903, was raised with his three brothers as sons of the city’s deputy chief rabbi.

His father David Kessler identified with the Haskalah (Jewish enlightenment) movement and had earned a PhD in Semitic languages and theology from the University of Vienna prior to his rabbinical training. Even after Austrian Czernowitz became Romanian Cernăuți, the Kesslers — like many middle- and upper-middle class Jews there — continued living their lives in German (A Doctor’s Memoir was translated from German by the late Margaret Robinson).

Arthur followed his father to the University of Vienna, but on a far more pragmatic track: Medicine. After a mandatory year as a Romanian army doctor, he joined a government hospital in Germany, but was fired upon Hitler’s rise in 1933 and returned to Czernowitz. He became a highly regarded physician with a specialty in allergies.

A few years later he met Judith Schulsinger, my grandmother — a stylish and strong-willed merchant’s daughter whom he had met in Vienna.

They had their first child in August 1940. It was a few weeks after the Soviet invasion, and the new regime demanded all newborn babies carry Russian names. For their daughter, my aunt, they chose the name Vera.

The newly arrived Soviets, ever-resourceful, tapped him as director of a local hospital.

But their presence would be short-lived. Antonescu forged an alliance with Hitler, styling himself Conducător (Leader), Romanian’s analog to Führer or Duce. When Antonescu came to see even the Iron Guard as a threat, he crushed it and seized sole power himself — but not before the Guard managed to murder at least 125 Jews in the January 1941 Bucharest pogrom.

When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, Hitler’s new Romanian allies joined what Antonescu exalted as a divinely-guided “crusade” against “Judeo-Bolshevism.”

A week later saw one of the bloodiest pogroms of the entire war: The murder of at least 13,266 Jews in the city of Iași by Romanian and German troops, local police and civilians.5

Within weeks Antonescu’s troops had recaptured the lands lost to the Russians the year before in Bukovina and Bessarabia. By August their gains extended even further, including a swathe of Soviet Ukraine between the Dniester and Bug rivers that had never been part of Romania. They called it Transnistria — “across the Dniester” (not to be confused with the modern breakaway statelet of the same name).

Romanian troops, with German assistance, waged a months-long siege of the Black Sea port of Odessa. A week after the city fell, Romanian soldiers and German Einsatzgruppen capped the victory with another blood-drenched pogrom of the city’s large Jewish population — citizens not of Romania but of Soviet Ukraine. Between 25,000 and 35,000 of these Jews were shot and burned over three days in the Odessa massacre of October 1941.

Now “cleansed” of “Bolshevists”, Odessa became capital of Romanian-occupied Transnistria.

Having been head of a hospital during the so-called “Russian Year,” Arthur Kessler was arrested as a “communist agent” and given a brief show trial. Bribes from my grandmother (whose weakness for fur-collar coats could have itself refuted the “Bolshevik” charge) got him released.

But in September 1942 he was picked up again, detained, and deported to Transnistria with alleged communists and Soviet sympathizers. He was nearly 40.

“Until recently, the history of the Romanian displacement and genocide of Jews and Roma in the era of World War II had largely remained unincorporated” within Holocaust studies, writes Leo Spitzer, the Dartmouth emeritus history professor who edited the book, in the introduction (I also helped with editing).

“Fascist-era crimes committed by Romanians were not incorporated into Romania’s collective self-awareness,” Spitzer adds, noting that the archives stayed mostly locked until the fall of the Ceaușescu communist dictatorship in 1989. Moreover, the “sites of the camps and ghettos in the area of the former Transnistria itself have remained largely unacknowledged and unmarked in present-day Ukraine.”

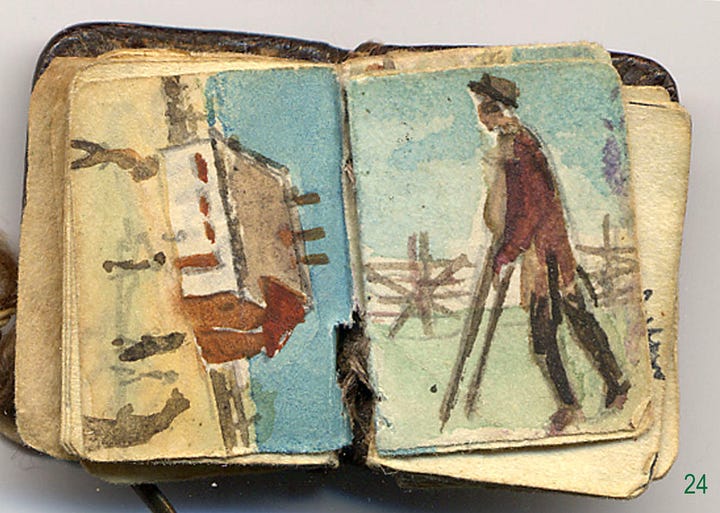

I hope in a subsequent post to recount my grandfather’s deportation and incarceration through excerpts from his memoirs. That post will center on the mass-poisoning at Vapniarka that is unique even in the macabre annals of the Holocaust (in 2019 we donated his archive of documents and artifacts to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington).

That post will complete my grandfather’s postwar story of escape to Mandate Palestine, welcoming a second child (my father), starting professional life anew, treating the paralyzed Vapniarka survivors for decades free of charge, and leading a successful fight for their reparations from Germany.

For my own part, I remember him as a kind, soft-spoken grandfather, ready with a chocolate bar (always the same kind) for my brother and me whenever we visited him and Judith in their walkup Tel Aviv apartment.

He was a man who wore a jacket and tie long after anyone else in Israel did, who was widely loved and admired in his new homeland. Hundreds of disabled survivors owed him their lives and whatever mobility they had left — one grateful survivor sponsored an entire hospital wing, anonymously, in his name.

He died in 2000, when I was 18 and he was nearly 97. But all of that is a story for another post.

For now I’ll limit myself to two short passages from his book. They give a sense, I feel, of the dense, lean, understated but deeply affecting tone in which my grandfather recounts the darkest chapter of modern history, and the darkest of his own life.

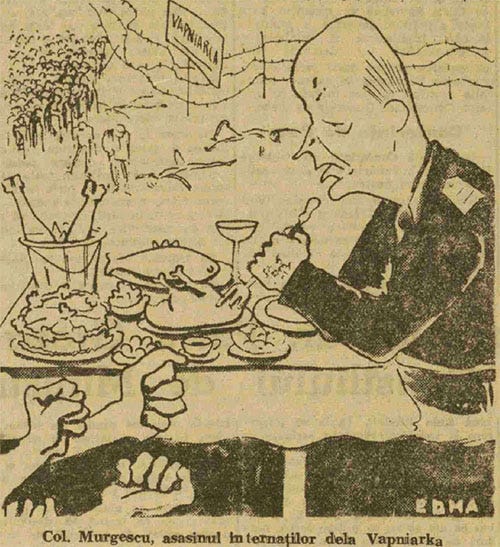

One is his description of the camp commandant — a particularly odious, drunken and sexually exploitative middle-aged colonel named Ion Murgescu.

What a scene! Feet planted apart, his jowled face and fat neck are thrown back, a martial specimen indeed. In Napoleonic fashion, he carries his right hand between his coat lapels and thus diminishes the disproportion between chest and belly…

His speech is short:

“On the slope behind the camp you can see the graves of 550 people who were in the camp before you. They died of typhus. Try to do better if you can.”

“Hope springs eternal,” Dr. Kessler writes elsewhere, clutching a scrap of optimism amid the prevailing gloom.

“Hopelessness is the verdict of a third party—the one affected doesn’t accept it.”

Part II of this post, “The poison peas,” is here.

In late 1937 the king allied briefly with the venomously anti-Jewish poet-politician Octavian Goga, who promptly revoked the minority-protection treaty and stripped one-third of the country’s Jews of citizenship.

Germany agreed to pay reparations to survivors of the Iași pogrom only in 2017.

Critical information. Too many people are unaware of the crimes committed by Hitler’s reliable ally Romania. Thank you, and may your grandfather’s memory and his witness continue to be a blessing and inspiration.

Kudos to an excellent introduction to an under-reported corner of WWII. Thank you for the historical context and sharing your grandfather’s painful, horrific experience as a Romanian Jew during the Holocaust. I learned something today. Thank you again.