When Mencken came to Palestine

How America’s wickedest pundit – whose views on Jews were ‘mixed’ – became its unlikeliest Zionist

Last week, as data rolled in on Donald Trump’s election victory, online mentions of H.L. Mencken grew exponentially. Mencken was a skeptic of electoral democracy (among other things) and eminently quotable for those left, right and center who see Trump as proof of how easily democracy can slide into demagoguery. Or as Mencken put it, into “the worship of jackals by jackasses.”

This post, however, is not about Trump but about the so-called Sage of Baltimore himself, his visit to Mandate Palestine exactly nine decades ago and his unlikely conversion to Zionism. Please subscribe and share…

H.L. Mencken was America’s preeminent pundit in the first half of the twentieth century. From the 1910s to 40s he churned out copy almost daily — some 10 million words in all — slinging his poison-tipped arrows at religion, democracy, the equality of mankind, and most everything else Americans hold dear. He had an extraordinary gift for language — all these decades later, the prose still rings, the barbs still sting.

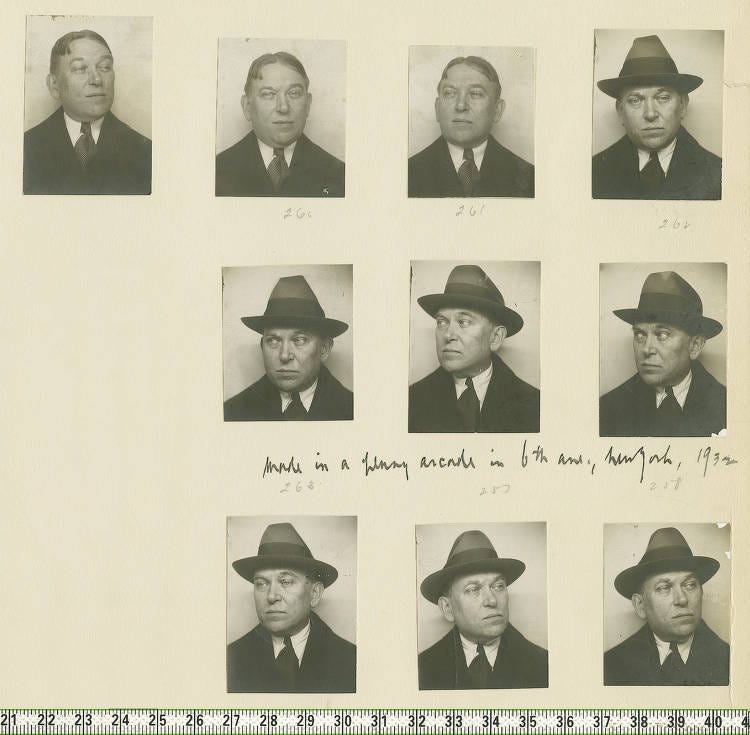

The son of a self-made cigar baron, Mencken was an autodidact who never attended college. He lived almost his entire adult life in the West Baltimore townhouse where he had been raised, in the sole company of his caretaker and sandwich-maker: his mother. He rarely left Baltimore — let alone America — if he could avoid it. But in 1934 he took his wife Sara (he’d married at 50, suspiciously soon after his mother’s death) on a trip to Europe and the Holy Land in the tracks of Mark Twain’s travelogue The Innocents Abroad.

His dispatches from British Mandate Palestine — four short newspaper columns, and a later chapter of his autobiography — are acerbic but also revelatory. Here we find the curmudgeonly atheist lost in child-like awe amid the biblical landscapes, and a man whose sentiments on Jews were at best “mixed” falling headlong for the Zionist project.

So taken was Mencken that upon his return he gathered the columns into a slim book, complete with Hebrew title page, and had 25 copies privately printed. He called it Erez Israel. At first it looks like a typo (the Hebrew “Land of Israel” is usually rendered as “Eretz Israel”) until the reader remembers that for Mencken — of entirely German stock and fluent in the language — the final letter of the alphabet is pronounced as in Mozart, or zeitgeist. Or Herzl.

Mencken was master of the the lede, the opening sentence of an article or essay. His first report from Palestine (written for the Baltimore Sun but widely syndicated) began with characteristic irreverence, but interspersed with unusual flashes of sincerity:

The guide books give so much space to the sacred places, real and bogus, of the Holy Land that there is none left for the scenery, which is a pity, for it is lovely beyond words, and, in certain of its aspects, probably beyond compare. The curious thing about this loveliness is that it runs the whole scale from the paradisiacal to the infernal, and often within the space of a few miles.

He was impressed by the Zionist towns — particularly “brisk, sunshiny, spick-and-span Tel Aviv” — but less so by Jerusalem, “only a kind of mummy today.” More than anything he was dazzled by the communal farms, the kibbutzim.

Around a bend one comes upon a vast warm basin of vivid green, criss-crossed in farms and with charming red-tiled villages climbing up the slopes. The red tiles are notice that Zionists dwell within, and wherever there are Zionists there is deep plowing, and with it tractors for the plows, and fat, sleek cows …

And every ten miles or so there is a village with a gasoline station, and a hardware store, and a stand that sells chocolate bars and chewing gum, and a shiny new [British] police station of concrete, with a white turret on top of it, pierced for machine guns.

And just as Mencken was master of the opener, he likewise set the standard for the closer — the “perfect fast ball,” per one admirer, “centering in the catcher’s mitt with an absolutely satisfying smack.”

Not one for coyness, he made his sympathies plain.

In the face of all this the poor Arabs simply curl up and fade away. They still scratch the stonier patches with their home-made wooden plows, unchanged since Abraham’s time, and on the hilltops they still live in their cold, tomb-like villages, along with their donkeys, their camels and their bitter reflections, but it is plain to see that most of them are not long for this world.

If the law of the Koran still ran in Samaria they would descend anon and help themselves to their neighbors’ forage, but today the whole of Palestine lies under Magna Carta, and larceny is discouraged by cops on motorcycles.

Subsequent days only cemented his admiration — for the Land and its new arrivals.

“The Jordan itself is no great shakes,” he wrote the next day. “But at the forlorn little Arab town of Semakh, hard by Magdala, it widens out into the Sea of Galilee, and around the shores of the sea is some of the loveliest scenery I have ever laid eyes on. Not even Switzerland can surpass it.”

The kibbutzim, “seen from a distance, are extraordinary [sic] charming, he wrote on the third day.

“Jewish achievement in that land of primitive agriculture is really remarkable,” he gushed to a gaggle of reporters who swarmed his ship lounge upon his return. The settlement of Kibbutz Ein Harod, not far from the Biblical Armageddon, “is one of the finest I have ever seen in my life.”

The British, he said, were “playing their usual politics” and using the Jews as “suckers” to solidify their own control on the eastern shore of the Med.

“When he returned to Baltimore, he spoke of little else,” wrote Marion Elizabeth Rodgers in American Iconoclast, the most recent in at least half a dozen major biographies in the seven decades since his death. He joked to his publisher Alfred A. Knopf, an assimilated Jewish Germanophile, “that he hoped to convert him to Zionism.”

But Mencken later admitted that he had filed his Palestine stories in such delirium that they had been “rather superficial.” Nearly a decade later, in the midst of World War II, he wrote a more considered account — a chapter in his autobiography Heathen Days that he called “Pilgrimage.”

It is — from the first words of its über-Menckenian lede — strong stuff.

I was fifty-three years, five months and sixteen days old before ever I saw Jerusalem, and by that time, with Heaven itself beginning to loom menacingly on the skyline, my itch to sob at the holy places was naturally something less than frantic.

I had not, in fact, gone to Palestine for the purpose of touring them, and had no intention of doing so; the only aim that I formulated to myself, in so far as I had any at all, was to visit and investigate the ruins of Gomorrah, the Hollywood of antiquity and the only rival of Sodom in the long and brilliant chronicles of sin.

Disappointed to learn that no one knew where to find the ruins of either Sodom or Gomorrah (their exact locations remain unclear today) he reluctantly called off the expedition.

“My decision left me with some unexpected leisure on my hands, and I employed it in moseying about Jerusalem, the glory of Israel as Ireland is of God. It turned out to be a town of about the size of Savannah, Ga., or South Bend, Ind.”

“There had been, a short while before, some gang fights between Jews and Arabs, and they were destined, a little while later to fall upon one another in the grand manner” — namely the Great Arab Revolt.

Still, “I was not molested, though I was warned by an English cop that some sassy Arab might have at me with a camel flop as an infidel or some super-orthodox Jew might hoot me as a chazirfresser” — that is, a “pork eater.”

Mencken knew enough German, and enough Jews, to grasp Yiddish reasonably well (he later recalls the rough cobblestones sending a British copper onto his “tochos.”)

When a young Jewish Agency representative offered to drive him to Galilee, the old crank agreed (after the staffer tells him he has family in Baltimore). It turned out, he wrote, to be “one of the most charming trips I have ever made in this life.”

The kibbutzim “interested me greatly, if only because of the startling contrast they presented to the adjacent Arab farms,” one “so striking as to be almost melodramatic.” The Jews “lived in glistening new stucco houses recalling the more delirious suburbs of Los Angeles, and their animals were housed quite as elegantly as themselves.”

The Arabs, by contrast, “are probably the dirtiest, orneriest and most shiftless people who regularly make the first pages of the world’s press … Never, even in northwestern Arkansas or the high valleys of Tennessee, have I seen more abject and anemic farms.” Arab villages “resembled nothing so much as cemeteries in an advanced state of ruin.”

Terrible stuff, yes. Profoundly offensive. But the writing, it has to be said, is unignorable. A retrospective in Paris Review a few years ago dubbed the so-called Sage of Baltimore “Unforgivable and Unforgettable.”

That strikes me as about right.

Judging just by these excerpts, it is fair to concede that Mencken was not inordinately fond of Arabs. But what has long dogged his reputation are his checkered comments, both public and private, about Jews.

For decades scholars have debated the extent of Mencken’s antisemitism, not least in Menckeniana, the annual magazine published by Baltimore’s central library (see here, here, here and here, for example). David S. Thaler — a leading (Jewish) Baltimore real estate figure and longtime Mencken scholar — gave the library’s 2015 Mencken Memorial Lecture on the “paradox” of the writer’s ties to Jews, and even wrote an entire book on the topic.1

On one hand, a disproportionate number of Mencken’s close friends and colleagues were Jews. These included Knopf; George Jean Nathan, his decades-long co-editor of his popular magazine The American Mercury; and his assistant and eventual successor there, Charles Angoff.

On the other hand are his writings, both public and private.

In a 1918 introduction to Nietzsche, we find these indelible lines: “The case against the Jews is long and damning; it would justify ten thousand times as many pogroms as now go on in the world.”

In Treatise on the Gods, his 1930 broadside against any and all religion, he offered this:

The Jews could be put down very plausibly as the most unpleasant race ever heard of. As commonly encountered, they lack many of the qualities that mark the civilized man: courage, dignity, incorruptibility, ease, confidence. They have vanity without pride, voluptuousness without taste, and learning without wisdom.

That debate grew saucier (as Mencken might have put it) with the publication of his diaries in 1989. In them, he takes an unbecoming interest in who is and isn’t a Jew. He is pleased to learn that an editor, Richard Danielson, “is not a Jew” despite his potentially Mosaic surname. The wife of the writer Sinclair Lewis, however, is “a young Jewess rejoicing in the name of Marcella Powers.” When Lewis wants to sell a novel to Hollywood, he scribbles, “The Jews have offered him $30,000.” And so forth.

Mencken treasured all things German: Beer, Beethoven, and above all Nietzsche, on whom he wrote the first primer in English early in his career.

Upon Hitler’s rise in 1933 he dismissed him as an “idiot,” “lunatic,” “maniac,” and a “preposterous mountebank.” He thought it inconceivable, wrote the critic Terry Teachout in his own Mencken biography, “that such a buffoon could long pull the wool over the eyes of the most civilized people on earth. Sooner or later they would have to catch on.”

Mencken treasured all things German: Beer, Beethoven, and above all Nietzsche

When World War II began he kept studiously quiet. He remained bitter over Americans’ anti-German hysteria in the First World War (a hysteria, and a war, long since forgotten in America), and his impulses were in any case libertarian and isolationist.

“I still have not heard him say a word against Germany,” Knopf remarked early in the war. “He is personally about the kindest and most sentimentally generous man I’ve ever known but these large areas of discussion must simply be avoided.”

And by 1945, as the world learned that the ghastliest rumors of German atrocities were all true, Mencken remained “noticeably silent,” in Marion Rodgers’ words. “Mencken's characteristic reaction to subjects he found too disturbing even to contemplate was a stony-faced silence.” He found himself unable to sleep, increasingly disturbed by nightmares.

That year, as he prepared a revised edition of Treatise on the Gods, he scrubbed the line designating the Jews “the most unpleasant race.” Words that read as vintage Mencken in 1930 — and which he might have applied to any number of groups — now sounded callous, even cruel, when ascribed to the primary victims of Nazi mania. Eventually, even Mencken came to recognize that “better than the rest of us, they sensed what was ahead for their people.”

This embarrassed silence on the greatest crime in modern history — and from the most irreverent and voluble of pundits — is the most damning chapter in Mencken’s life.

“Unforgivable” is right.

The most charitable interpretation is one offered by the late Matt Nesvisky, formerly a senior editor at the Jerusalem Post:

Mencken’s supporters … insist his antisemitism merely reflected the prevailing prejudice of his time. More persuasive is that Mencken was an equal opportunity offender. Truth is, he despised nearly everybody. Throughout his career, Mencken vented his spleen against the English, the Irish, the Italians, the Asians, African Americans and, not least, most of his fellow white Americans.

As we have seen, this list could also have included the Arabs. Mencken’s missives from Palestine drip with a disdain for Arabs far beyond what he reserved for the Jews. A few more excerpts will suffice:

The Arabs of Palestine “breed like flies but die in the same way,” he wrote, and their “draft animals look as starved and flea-bitten as they do themselves.” He marveled that “land that formerly supported only a few malarious or sunbaked Arabs” was being converted into fertile farms housing thousands of Jews.

The Arabs “blamed the effendi landlords in Cairo and Damascus for selling them out to the Jews,” while the Jews hoped their own example “would lift these degraded step-brothers out of their ancient shiftlessness and imbecility.”

He reckoned Zionism’s odds for survival at about even — but not because of any errors in planning or execution:

On the one hand, it is being planted intelligently and shows every sign of developing in a healthy manner. But on the other hand there are the Arabs—and across the Jordan is a vast reservoir of them, all hungry.

He admired the Jews he saw farming near Armageddon with rifles strapped to their back, but “it was usually in the back that the brave Arabs shot them.” Foreshadowing the Arab Revolt, which erupted exactly two years after his first dispatch, he ends his essay thus:

Over the dust of the immemorial and innumerable dead some Jewish colonists were driving Ford tractors hitched to plows … I noticed that the earth their plowshares were turning up was redder than the red hills of Georgia. In the afternoon sunshine, in fact, it was precisely the color of blood.

In May 1948 the British Mandate ended and Israel was born. News from the Promised Land again drew his attention, and he scoured the Palestine Post for the latest. “Even the advertisements in the Post fascinated him,” wrote Rodgers, and he wrote one of its journalists, the Vienna-born Paula Arnold, complaining (likely in German) that his copy hadn’t arrived in the mail.

A month later he gave a recorded interview to a Baltimore Sun reporter — the only time his voice was ever captured for posterity. A few months after that he suffered a stroke. He would live seven more years but never write again.

I discovered Mencken during the pandemic.2 Over those lazy two years I read more of him than of anyone else (many of his books are old enough to be in public domain).

And while I’m generally skeptical of cancelation (would the world be richer without Chopin, genius and Judeophobe?) over time I realized that his non-reaction to the Holocaust was rendering the rest of his work distasteful to me. Much as I love the writing, it was ever-more difficult not to loathe the writer.

One of the best biographies of Mencken in recent decades is Teachout’s “The Skeptic.” The next one (for there is bound to be another) could be called “The Anti-Semite,” but that would cover just part of the story; it would work better as a chapter alongside “The Anti-Puritan,” “The Anti-Southerner,” and “The Anti-American.”

A better title might be one borrowed from another master satirist, hailing neither from Baltimore nor Berlin but from seventeenth-century Paris.

The Misanthrope.

My first taste of Mencken was his astonishing 1917 essay on culture (or lack thereof, in his view) in the American South: “The Sahara of the Bozart” (i.e., the Beaux-Arts).

Nice piece. I discovered Mencken when my history teacher in school (in Switzerland) showed an episode of Alistair Cooke's documentary on America. At the next occasion I purchased a book of his columns (I still have it). That was in 1975... I have, like yourself, read pretty much everything, whereby a fair amount of his writing while fun (hyperbole) and acidic, does get tiresome. The broad brush strokes are dull. But overall he nails the USA perfectly, and some of his observations are prescient. The problem of overpaying reporters, for example, and the incredible reports from the Scopes Trial,... he even warns about evangelical hatred of everything modern, suggesting we keep an eye on them because otherwise they will "devour us." The "mountebank" Bryan (who "radiated hate like heat from a stove") was a slightly more sincere Trump figure....

So Mencken and the Jews... well, there's also the discussion of Mencken and racism. The jury is out, whereby I myself wrote once about Mencken saying he is an "equal-opportunity insulter." What he disliked was the kind of moral groupthink that many religious and political communities. His incredible writing was compulsive, he read many things, commented on all sorts of subjects, spotted talent and was a great reporter with an eye for details that others would not see or would not report on out of some false sense of decorum. My criticism: He seems to have stopped mostly at Nietzsche when it came to thinking. With Nietzsche, he found a lane, and hardly every got out of it.

Having said that: When election time rolls around, I always read my Mencken. He spotted Donald Trumps and Copelands and RFK Jrs all over the place. He had the courage to write hilarious lines about Aimée McPherson (one of the earliest scammers of the prosperity gospel), noting discreetly the prurience of her thick auburn hair and her hips... He had no fear of being politically incorrect... he did not give a damn about the "moral gaze" of others, and maybe that is what we need today.

Interesting to think about this famous (and reclusive) pundit of 90 years ago in comparison to some of the more colorful personalities on Substack, podcasts, or YouTube.