Notes from underground

Scenes from a bomb shelter (mine), and thoughts on the present apocalypse

A note: After rebranding this channel as “Undercurrents” just last month, I’m now re-rebranding it as “Subterranea.” Seems fitting.

TEL AVIV — Readers of this Substack know I try to steer clear of the news. This channel’s description explicitly promises: “Not current events.” After all, I figure, Israel-Palestine punditry already rolls across the Web like a river, and hot takes like an ever-flowing stream.

But exactly a week ago, as you may have heard, the apocalypse arrived. Or a very great reckoning, at any rate. And it struck me that many of you — at least those living far from these blessed shores — may be wondering what it’s like to be on the receiving end of hundreds of ballistic missiles.

So here goes.

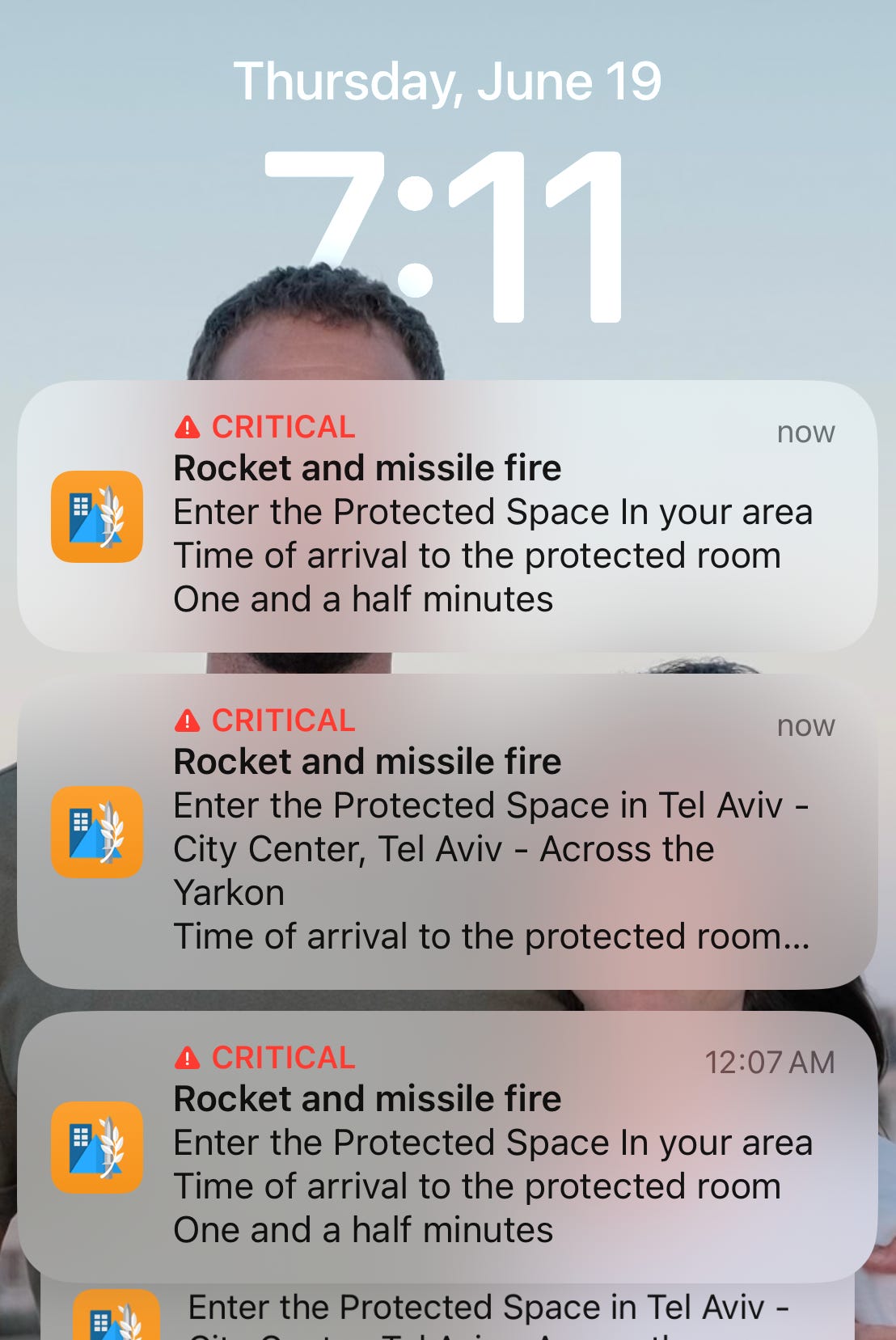

It begins with a phone alert from IDF Home Front Command that a missile barrage has been detected. That leaves a brief window (30 minutes at first, now closer to 10) to get to safety.

Israeli law requires new (or newly renovated) apartments to have reinforced rooms. Many newer buildings also have reinforced common areas. Our building dates from the 50s (the work of the pioneering female Bauhaus architect Lotte Cohn, but that’s really for another time), and affords no such protection.

So for us, an alert means rushing down the two floors of our building, crossing the playground next door and descending the steps of the public shelter underneath it.

On Friday, the first full day of the war, I posted a video to Twitter of what that walk looks like for us. You can see it here.

The shelter, really a bunker, is some 20 feet underground, 100 square meters wide and fits well over 100 people (with ample room for baby carriages and dogs). Folks tend to be calm, resilient and good-humored about the whole thing — Israelis are often at their friendliest during crisis, their gallows humor given its fullest play. One neighbor stoically descended the shelter steps nursing a beer bottle.

I took this video on Friday night:

The following days brought the same routine: Typically one missile alert during the day, then several overnight. So we decided that each night, we would bring yoga mats, some water and food, and ride out the night underground.

We’ve done that for the last week, and each night I documented the shelter scenes and posted them to Twitter.

Here, here and here, for example. And here and here.

Most of our neighbors, however, preferred to sleep in their beds. So whenever a missile alert sounded, the shelter would again fill to capacity. We would hear a few booms of missile interceptions (a few times they were particularly loud — direct hits, like the devastating ones on central Tel Aviv and neighboring Bat Yam).

A week into this routine, we’re feeling a certain fatigue — one friend described it as “jet lag without the vacation.” There’s also a certan cabin fever; for a week haven’t been anywhere but home and the shelter. It’s a bit like the start of COVID, but with one-ton warheads.

So much for our personal experience.

More broadly, what has struck me most is the nearly complete consensus across Israel (or across Jewish Israel, anyway) that this offensive was necessary.

A poll released today by the Israel Democracy Institute found 82 percent of Jewish Israelis support the timing of the operation (codenamed, biblically, as Rising Lion), including 57 percent of those who identify as left-wing. Notably, two-thirds of Jewish respondents said Benjamin Netanyahu's considerations were security-related, with just one-fifth saying he was driven by political motives.

Despite the prime minister’s cratering approval rating (around 30%) — and widespread suspicion over his motives in prolonging the Gaza war — not a single member of a Jewish-majority Knesset party raised his or her voice to protest the strike. Rather, his fiercest critics lined up in praise.

“Netanyahu is my political rival, but his decision to strike Iran at this moment in time is the right one,” wrote opposition leader Yair Lapid. “The whole country is united in this moment, when faced with an enemy sworn to our destruction, nothing will divide us.”

“It’s not the right moment to do politics,” he told reporters. “Yes, this government needs to be toppled, but not in the midst of an existential fight.” On Tuesday he met with Netanyahu for a security briefing — the photo that emerged was notably cordial. (The home of Lapid’s son, and year-old granddaughter, was heavily damaged in the Tel Aviv strike.)

Alon Tal, an American-Israeli environmentalist and former lawmaker with Lapid’s Yesh Atid party, penned an op-ed titled, “When a Rising Lion Turns Doves into Hawks.”

“After October 7th, I take seriously Tehran’s doomsday clock—the public timer which counts down the time until the 2040 deadline, which Iran has set for Israel’s destruction to be complete,” he wrote. “There is no doubt that this violent Islamic regime wouldn’t hesitate to use a nuclear capability to finish the job.”

Yair Golan, chair of the Democrats party (a self-described “liberal-democratic” merger of Labor and Meretz), aired similar sentiments.

“A strong people, a determined army, and a resilient home front. That’s how we’ve always won, and that’s how we’ll win today too,” Golan tweeted. “The decision to act was correct,” he wrote, calling the offensive “a rare and admirable military achievement.”

Finding opposition to this war within Jewish Israel requires going to the furthest reaches of the left, to the peace movements Standing Together or B’Tselem. And even their criticism tends to be oblique, aimed at the timing of the strike or the distraction it provides from Israel’s actions in Gaza or the West Bank.

The war is far less popular among Israel’s Arab citizens; the abovementioned poll found just one in ten of them in support.

Indeed, the only hint of protest in the Knesset came from Ayman Odeh, head of the majority-Arab party Hadash-Ta’al. After an Iranian missile struck a home in Tamra, Lower Galilee, killing four members of the Khatib family, he blasted the Netanyahu government for not providing adequate public shelters to Arab municipalities.

“No to war with Iran, enough of the war of annihilation in Gaza,” he wrote. “Agreements save lives. Dictators think wars save them.”

This unusually broad consensus is perhaps not surprising. This is, after all, a reckoning several decades in the making.

As I’ve written in Foreign Policy:

Twenty years have passed since Israel first raised the alarm over Iran’s nuclear program, 10 years since Iranian dissidents revealed the enrichment plant at Natanz, and roughly two since pundits started predicting an Israeli attack against the Islamic Republic.

I noted that Ronald Reagan didn’t keep Pakistan from building a nuclear bomb, nor did Bill Clinton stop North Korea from doing the same. And I quoted an interview in Haaretz with an anonymous “key decision maker” — almost certainly ex-premier Ehud Barak — who concluded:

We mustn’t listen to those who in every situation prefer non-action to action… Even a cruel reality must be looked at with total clarity. Israel is strong and Israel is responsible, and Israel will do what it has to do.

I noted that Netanyahu, Barak and fellow champions of a strike were convinced that sanctions have been ineffective, that negotiations were at a dead end and that military action was therefore inevitable.

“Today, never have so many Israelis from across the political spectrum agreed that a military strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities could arrive within months.”

The article was from summer 2012.

From Israel’s perspective there is, the current war nonetheless carries one clear and present danger; that amid the justified pride in Israel’s martial prowess, and the shock over spilled blood and toppled towers, that another national imperative will fall by the wayside.

Along the fence surrounding the playground between our home and our shelter, someone hung a simple but unignorable reminder of that imperative. It’s an image noticeable for its ordinariness: Two men in their 20s, at a barbecue, gesturing as if hitchhiking at the side of the road.

They are twin brothers Gali and Ziv Berman, residents of a Gaza-area kibbutz and hostages of the mullahs’ proxy Hamas for 622 days.

The banner over their heads reads: “They have been looking for their way home for far too long.”