A ‘fanatic’ as long as he breathes: Ibn Saud vs. the grand mufti

In secret 1939 letter, Saudi Arabia’s founder warned Hajj Amin would lead Palestinians to ruin. He wasn’t alone

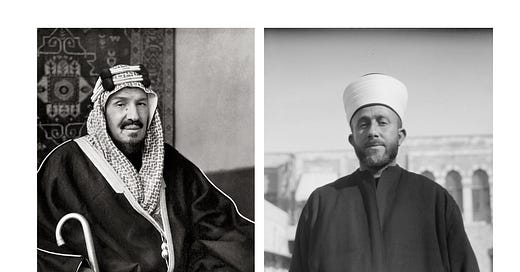

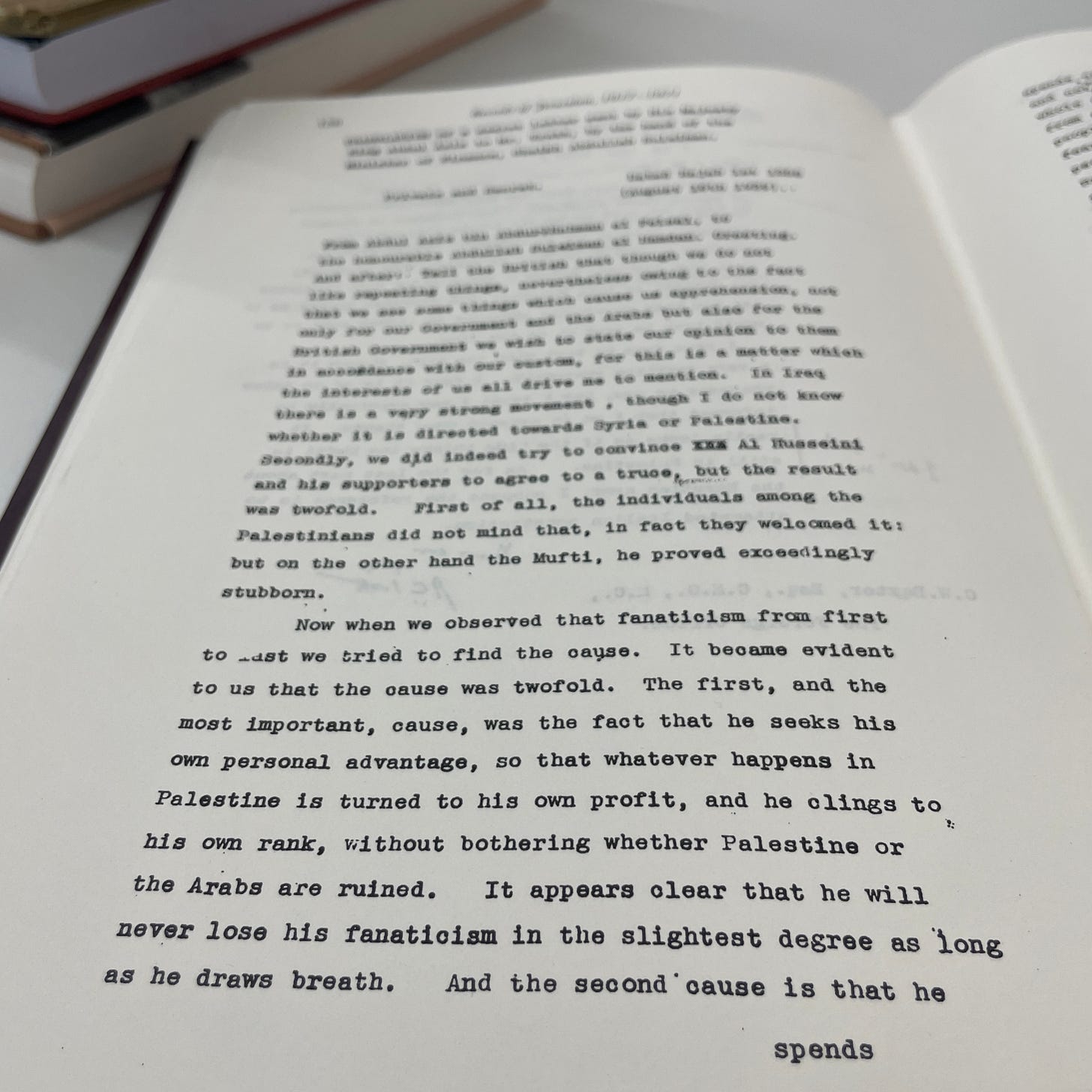

In mid-August 1939, two weeks before Hitler invaded Poland and launched the Second World War, a letter arrived on the desk of a British diplomat in Jedda. Four pages long, it was written in Arabic and carried only the Islamic date: The first of Rajab, 1358. The message was signed by “Abdul Aziz bin Abdul Rahman al-Feisal” — better known in the West as Ibn Saud — and bore the royal seal of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.1

“I desire that this should be a complete secret and should be confined entirely to yourself,” the king wrote. “Its dangerous character will be clear to you: but I felt I had to say it.”

The subject was Hajj Amin al-Husseini. The grand mufti of Jerusalem had fled to Beirut two years prior, wanted by Mandate authorities for spearheading the 1936-1939 Great Arab Revolt against British rule and the growing Jewish presence in the Holy Land. Ibn Saud wanted His Majesty’s Government to know: The mufti was not just anti-British and anti-Jewish — if left a free man, he would soon lead his own people, the Arabs of Palestine, to destruction.

Months earlier, in May 1939, the Chamberlain government had issued a White Paper that met most of the core Arab demands, severely cutting Jewish immigration to Palestine and setting it on course to independence as an Arab-majority state. The decision was met with mourning by the Jews and jubilation by the Arabs, but the exiled mufti stunned even his closest supporters by rejecting the offer. He insisted that not a single Jew be permitted to enter, that Arab independence be immediate, and that he be allowed to return to Jerusalem a victorious hero.

Ibn Saud sent his acolytes to Beirut to beg Amin to reconsider, and to reconcile with the British who two decades earlier had appointed him grand mufti, a lifetime position that made him the most powerful Arab and Muslim in Palestine. They found that although his circle welcomed such a truce, the mufti himself “proved exceedingly stubborn,” even “fanatic.”

When we observed that fanaticism from first to last we tried to find the cause … The first and most important cause was that he seeks his own personal advantage, so that whatever happens in Palestine is turned to his own profit, and he clings to his own rank [position], without bothering whether Palestine or the Arabs are ruined. It appears clear that he will never lose his fanaticism to the slightest degree as long as he draws breath.

The monarch continued:

The second cause is that he spends enormous sums of money, not only on himself and his friends and helpers, but throughout the whole country. There is no doubt that this all comes from some foreign hand, no doubt from those designing [scheming] people whom you know well.

That “foreign hand,” he implied, was the ascendant Fascist regimes in Rome and Berlin.

The diplomat, Alan C. Trott, translated the letter (“I have done my best with the text, though it is a very rambling statement”) and on August 21 forwarded it to the head of the Foreign Office Eastern Department. It was the same day the world learned the staggering news of the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact that removed the last obstacle to Hitler’s months-long threats to invade Poland.

The king implored London to “expel Al-Husseini completely” from the Eastern Mediterranean and “forbid him intercourse with anyone.” Still, he warned that these moves must not come “from a person like me, a Muslim and an Arab. Al-Husseini and his party must not think it is from me.”

The letter, buried in the Foreign Office archive and not previously published, underscores the fact that even before Hajj Amin’s notorious wartime collaboration with Hitler, influential Arabs were sounding the alarm that his intransigence, partisanship and radicalism would lead Palestine’s Arabs to catastrophe.2

Ibn Saud wasn’t the only one.

Musa Alami was a Cambridge-educated lawyer from a distinguished Jerusalem family who worked for many years in the Mandate’s justice system. He is one of the main Arab characters in my book Palestine 1936 and, judging by feedback, the one whom readers have connected to most.

A staunch Arab nationalist, his brother-in-law was Jamal al-Husseini, the mufti’s cousin and political boss.3 But Alami nonetheless cultivated decades-long friendships across Palestine’s ethnic and religious lines — both with British administrators and with prominent Jews.

One was with David Ben-Gurion, later Israel’s first prime minister. Another was with Ruth Dayan, a peace activist whose husband happened to be its defense minister. A third was Eliahu Elath (formerly Epstein), an Arabic-speaking graduate of the American University of Beirut who would become the Jewish state’s first ambassador to Washington.

In the 1970s, towards the end of his life, Alami repeatedly hosted Elath and his wife at his East Jerusalem home. Elath recalled his host as a man of “great personal charm,” a “seeker of justice and peace” who “reacted very patiently to the ideas of others even when he disagreed with them” (for example, Zionist Jews like himself).

But when speaking of the mufti, Elath recalled, Alami would often lose his composure. Hajj Amin was a “fanatic,” he would say — echoing Ibn Saud — bent on attaining and retaining power “by any and all means,” whatever the cost to Palestinians.

Alami lamented Amin’s role in the bloody 1929 Hebron riots, for which a British commission found him partly responsible and yet ultimately left him in his post. He mourned the infighting stoked by the mufti’s Higher Arab Committee during the 1936 revolt, when he was “relentless” in settling scores against opponents — particularly those Arabs contemplating any modus vivendi with the Jews.

When Britain sent a royal commission to examine the revolt’s causes and possible remedies, Alami pleaded with the mufti against a boycott. When the commission ultimately proposed dividing the Holy Land — history’s first two-state solution, with a diminutive Jewish state based along the coast — Alami urged him to at least consider the idea (he did not). Shortly thereafter, Hajj Amin fled Palestine, wanted by the British as the primary culprit for keeping the revolt aflame.

Finally, Alami told Elath, in rejecting the 1939 White Paper the mufti had “assisted the establishment of the State of Israel.” He quipped that his contribution to that end was “no less important” than that of his old friend Ben-Gurion.

Alami “constantly stressed the Mufti’s basic trait — extremism in thought and deed which ruled out any compromise,” Elath wrote. “No one, Alami said, not even his supporters in the Arab camp, thought of him as ‘moderate.’”

Hajj Amin’s World War II alliance with Nazism is only the best-known case in a career studded with self-sabotage and bad bets, both personal and national. When the war erupted he escaped Lebanon dressed as a woman, taking refuge in Iraq, where he backed a pro-Axis coup before again fleeing British clutches (Chamberlain’s successor, Winson Churchill, favored his assassination).

From late 1941 he based himself in Berlin, where he was Hitler’s chief propagandist and recruiter to the Arab and Muslim lands. He helped Heinrich Himmler enlist two divisions of Bosnian Muslims for the Waffen-SS, and worked doggedly to ensure that Europe’s Jews remained where they could be kept “under active control, for example, in Poland.”

“The mufti’s anti-Semitism and collaboration with the Nazis is beyond all serious question,” writes Gilbert Achcar, a Lebanese scholar, in his book The Arabs and the Holocaust. By 1945, Achcar notes:

With the accumulation of defeats under Husseini’s disastrous leadership, the only path still open to the Palestinians, if they were to avoid the catastrophe, the Nakba, was to shake off the political influence of this disreputable individual once and for all … This was not the path taken.

In 1946 the mufti fled Europe — and possible war crimes prosecution — and was welcomed in Cairo. There, despite his notorious wartime record, the newly created Arab League made him head of the reconstituted Arab Higher Committee.

Achcar concedes:

True, the Palestinian population nevertheless continued to regard the mufti as its leader, since no alternative had emerged. As with Yasser Arafat after him, Husseini continued, notwithstanding an endless series of defeats, to find a source of popularity in the very fact that his people’s enemies demonized him.

Britain had by then washed its hands of the Palestine problem and handed it to the United Nations, which created a Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP). But according to Alami’s authorized biography, the mufti “having evidently learnt nothing,” returned to his “usual sulky decision to boycott.” Alami writes:

He had never forgiven, nor ever would forgive, anyone whom he imagined might undermine his leadership, and was always determined to reassert his complete authority over the Palestine Arabs, whatever harm he might thereby do to their cause.

And when in November 1947 the UN finally voted to partition Palestine into two states, the exiled mufti wasted no time fomenting a renewal of violence. He played a key role in creating and recruiting for the Army of the Holy War, led by his cousin Abdel-Qader al-Husseini.

One path was never considered: A diplomatic agreement, one that would have arrested the growth of the Jewish presence and forestalled the 1948 war that turned some 700,000 Palestinians into refugees.

That year, as Arab losses mounted against the newfound Jewish state, the mufti declared an “All-Palestine Government” — predictably composed wholly of relatives and loyalists — claiming to control all the land from the river to the sea. In fact its writ extended only to a new, tiny sliver of territory, teeming with newly created refugees, wedged between Egypt and Israel: the Gaza Strip.

Per Elath, Alami believed the mufti had “betrayed his obligation to his people and brought upon them a disaster they would lament for generations.” The mufti’s actions cost many Jews their lives, Alami said, but they “lost the Arabs their country.”

As I wrote in my book:

This chieftain and icon of the Great Revolt was able to retain his leadership position even after brazen collaboration with the Nazis, but he could never recover the prestige he lost in the fiasco of 1948.

“No Arab historian has yet risen,” Elath writes, “to expose the mufti’s career and his leadership in one of the most critical chapters in Arab history, so that his people might draw the proper conclusions about the past and the future as well.”

Achcar calls Amin an “architect of the Nakba,” and sums up his place in Palestinian memory with two words: “embarrassed silence.”

But back to Ibn Saud.

It’s long been a common temptation in the Middle East — above all, perhaps, in Israel — to perceive one’s enemy’s enemy as a potential ally. In the 1930s, the Zionist movement shared an adversary with the Saudi dynasty in Hajj Amin; today they share one in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

For the last half-decade, thanks mostly to that shared enmity, Riyadh and Jerusalem have been rumored to be moving toward a historic normalization. In late September 2023, just weeks before Hamas’s October 7 onslaught, Riyadh’s crown prince (and one of Ibn Saud’s estimated 1,000 grandchildren) Mohammed bin Salman said normalization was getting closer “every day.”

But back in 1937, two years before his warning about the mufti, Ibn Saud hosted another Arabic-speaking British diplomat in his capital Riyadh. He could not understand, he said, London’s “strange attitude” toward the Jews, and the “still more hypnotic influence” they wielded over Westminster on the Palestine question.

After all, he said, the Jews were “a race accursed by God according to His Holy Book and destined to final destruction and eternal damnation hereafter.”

Our hatred for the Jews dates from God’s condemnation of them for their persecution and rejection of Isa (Jesus Christ), and their subsequent rejection later of His chosen Prophet. It is beyond our understanding how your Government, representing the first Christian power in the world today, can wish to assist and reward these very same Jews who maltreated your Isa …

I, Ibn Saud, have been your Government’s firm friend all my life. What madness then is this which is leading your Government to destroy this friendship of centuries, all for the sake of an accursed and stiffnecked race which has always bitten the hand of everyone who has helped it, since the world began?

The diplomat, H.R.P. Dickson, recorded that in the course of “the King’s rather forcible harangue” the monarch stressed that as sovereign over Islam’s holiest terrain, he was more than a merely temporal ruler.

Your Government should remember that I am the Arabs’ religious leader and so am the interpreter of the scriptures. God’s word to them cannot be got round.

Verily the word of God teaches us, and we implicitly believe … that for a Muslim to kill a Jew, or for him to be killed by a Jew, ensures him an immediate entry into Heaven and into the august presence of God Almighty.

What more can a Muslim want in this hard world?

Read more:

My 2023 deep dive on the secret testimony of Herbert Samuel, Mandate Palestine’s (Jewish) first high commissioner, on why he appointed Husseini as mufti in 1921 (The Times of Israel)

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was born just seven years earlier. It was the culmination of decades of warfare in the Arabian Peninsula, punctuated by the House of Saud’s capture of Mecca from the Hashemite dynasty in 1924.

Two weeks before Ibn Saud’s letter, Jerusalem Mayor Mustafa al-Khalidi warned Palestine’s high commissioner of the “disastrous effects of [the mufti’s] intransigence.” Khalidi would be the last Arab mayor of united Jerusalem.

In the postwar years Alami told Ronald Storrs (who as governor of Jerusalem had lobbied for Amin’s appointment) that the British “probably made a mistake not pushing him out altogether.” Albert Hourani, a scholar and activist, told Storrs he deemed the mufti a “disaster for the movement and blames no Jew for refusing to join any republic of which [he] would be President.”

As you say, Ibn Saud deserves credit for denouncing Hajj Amin.

But, it is important to note that the House of Saud had already been tightly intertwined with the family and theology of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab for two hundred years by Ibn Saud's time. The Wahhabi grip on the family has not ended.

Wahhabi thinking derives from the 13th-century Hanbali extremist Ibn Taymiyyah. It advocates brutal persecution of anyone deemed apostate, including anyone guilty of "bid'ah"-- even small changes to Islam as it was practiced in the 7th century. It's also big on destroying anything that might possibly connected with idolatry -- not only Buddhist figures, but also tombs and cemeteries of early Islamic heroes. Even music is deemed "haram" (forbidden), with public concerts, music in the schools, and radio banned.

Looking forward to your book on the Mufti!

I still don’t understand why Britain appointed him in the first place and why they didn’t finda replacement in1939.