My grandfather’s diary of Romania’s Holocaust: The poison peas

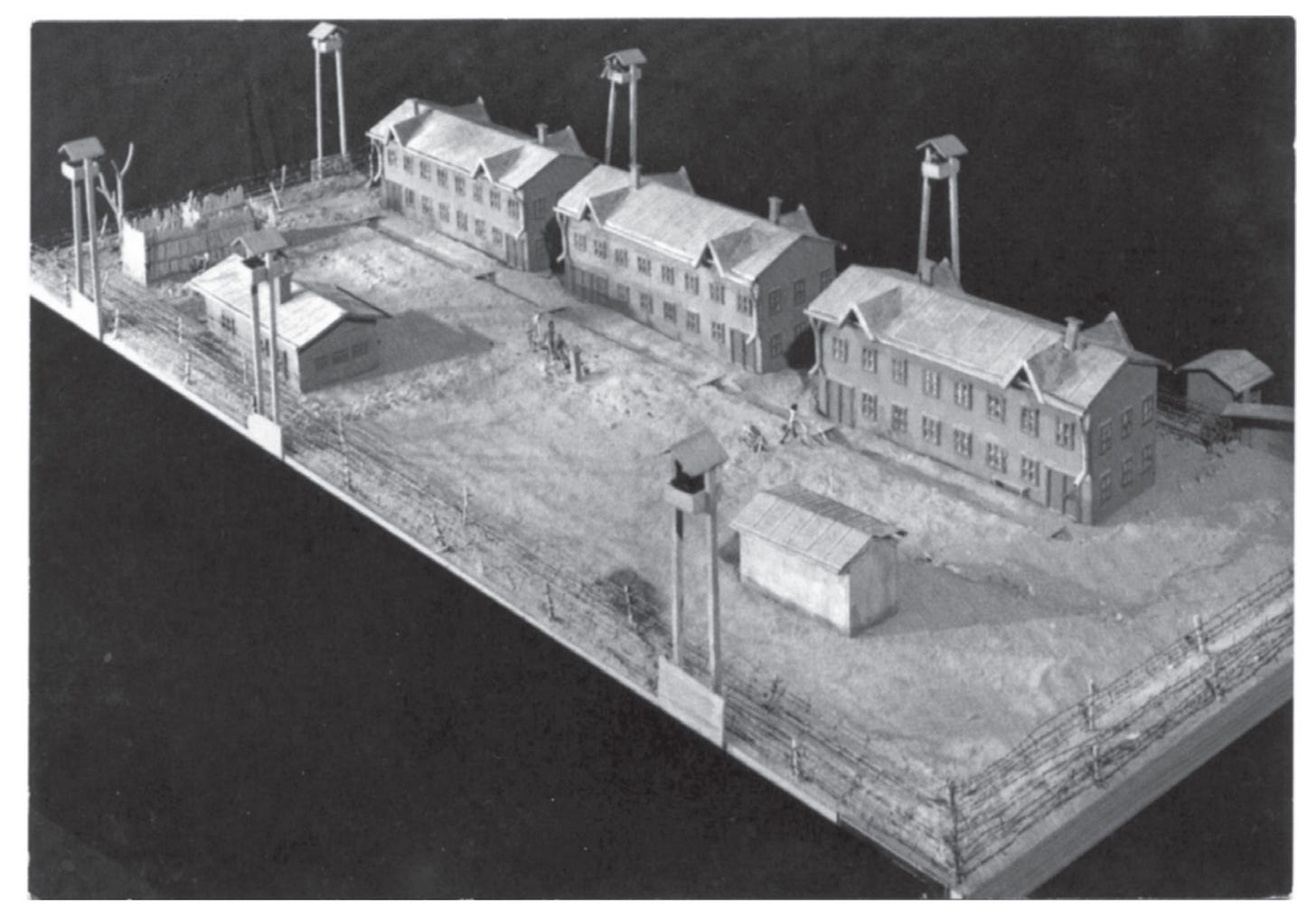

The story of Vapniarka, a mass-poisoning and paralysis unique in the grim annals of the Holocaust

A week ago, in Part I of this post (my first here on Substack), I introduced the “forgotten Holocaust” of at least 280,000 Jews at the hands of Hitler’s close ally Romania.

Here, in the second (and final) part, I offer a glimpse into my late grandfather’s newly published diary from one corner of that calamity: Vapniarka concentration camp and the mass-poisoning and paralysis of its prisoners.

Let us remember the good and valuable human beings who were left behind in shallow graves. . .

It was indeed a dismal time.

So writes Arthur Kessler in the prologue of A Doctor’s Memoir of the Romanian Holocaust, published last month.

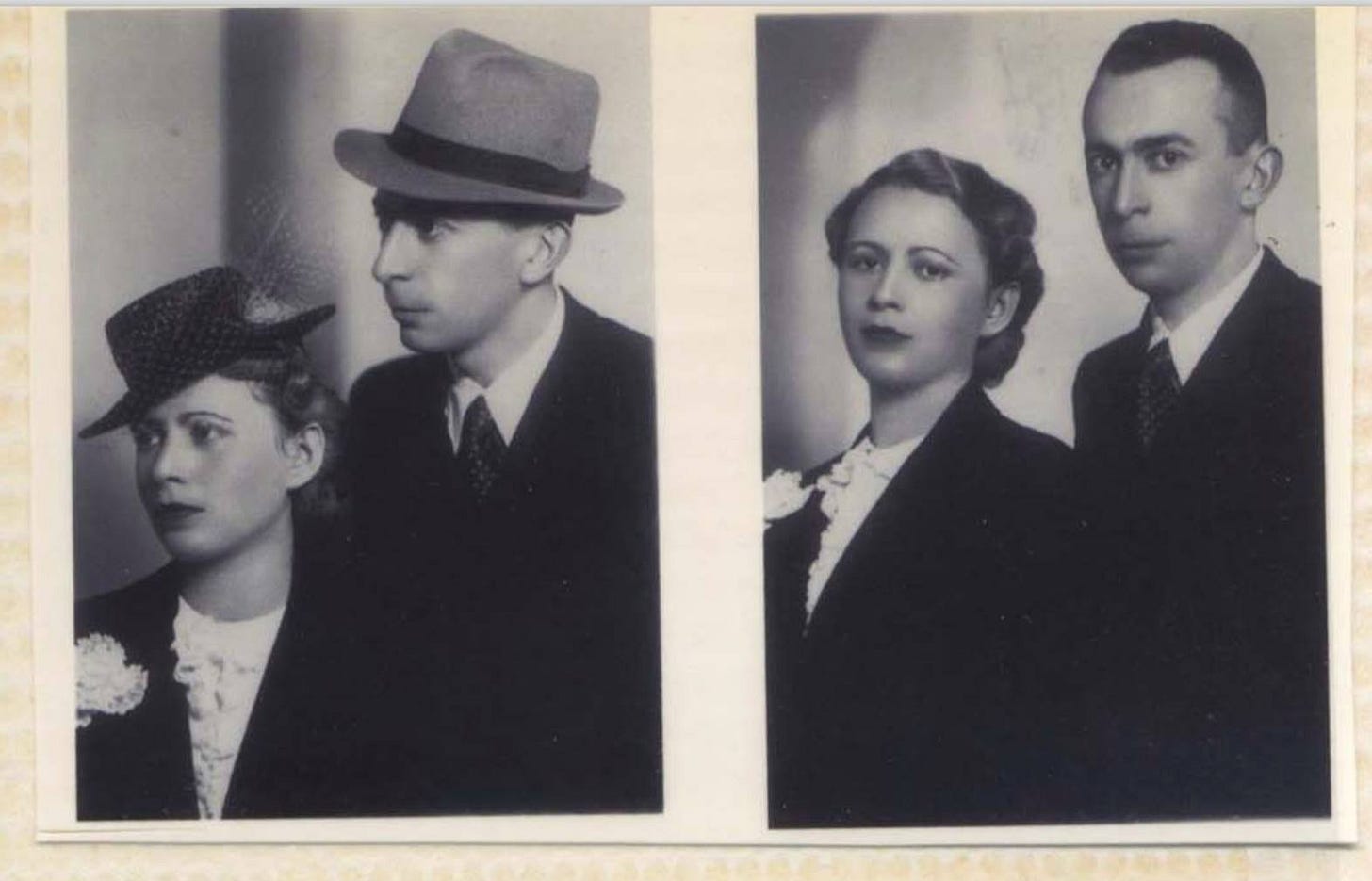

Kessler is a respected physician, nearly 40, living with his wife Judith and their infant daughter Vera in the Romanian city of Cernăuți, formerly known as Czernowitz.1

Having been appointed head of a hospital during the 1940-41 Soviet occupation of the city (again, see Part I), he was convicted in a show trial as a communist “agitator” by the fascist, Hitler-allied regime of General Ion Antonescu.

Imprisoned for five weeks in early 1942, he was ultimately released thanks to Judith’s machinations and a well-placed bribe.

By late summer 1942 tens of thousands had already been murdered in pogroms in Romania proper and Transnistria, Antonescu’s newly conquered swathe of Soviet Ukraine that he turned into Romania’s “dumping ground” for suspected communists and undesirables — chief among them, Jews.

Kessler’s wartime memoir begins, like so many other accounts of this “dismal time,” with the dreaded knock on the door. It was a commissar of the secret police, the same “crooked sadist” who had arrested Dr. Kessler the first time.

The commissar hauled him to the station, where police locked him up and inflicted the requisite verbal abuse (“the usual insults and mockery”), but released him the next day due to some unnamed intervention (presumably, more bribes from his wife).

The next day the couple were walking in the city center when he was detained yet again — now for the third time — but by plainclothes officers.

“We say goodbye, just in case,” Kessler writes. “I would dearly have liked to see the child once more.”

At the police station he met another 20 or so friends who have suffered the same unnerving but still unclear fate.

Rumors percolate: “We already know we are not bound for a nearby camp, but across the Dniester to Transnistria, which may mean extermination.”

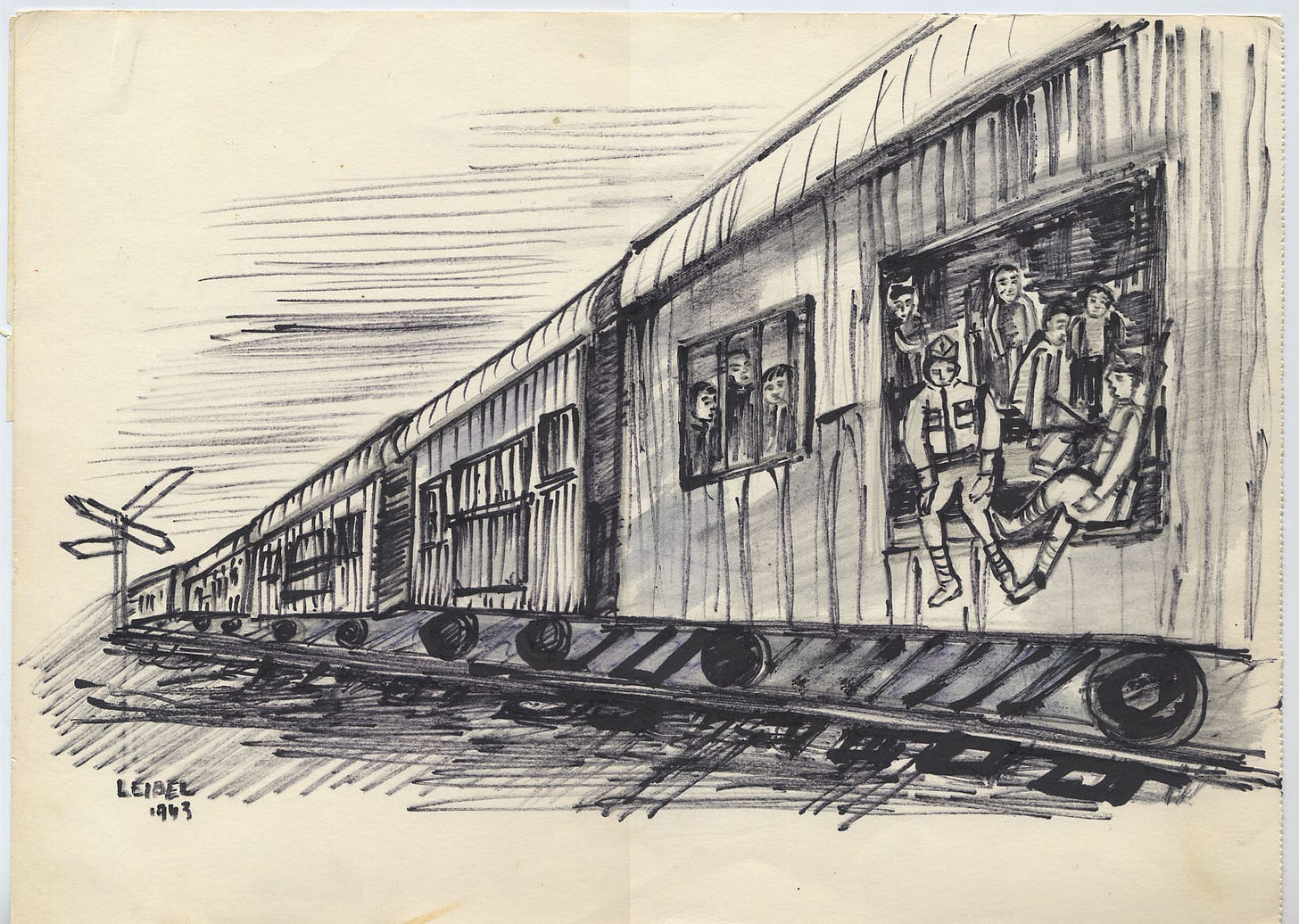

Soon the deportation began — a chain of railcars headed east toward Odessa and the Black Sea. Several times they switched cars, including, at least once, that symbol of the Nazi genocide: the cattle car.

They were guarded by gendarmes, a sort of military-police hybrid, who in his description were “simple farm boys, easier to bribe than a corporal who can read.” After several days the gendarmes informed the deportees that they had crossed the river into Transnistria.

On a stopover of several days in the town of Tiraspol, they learned their destination: Vapniarka.

“We leave our so-called homeland” — can anyone still call it a homeland after such betrayal? — “into no-man’s-land.”

“Tens of thousands have traveled this way before, none has come back.”

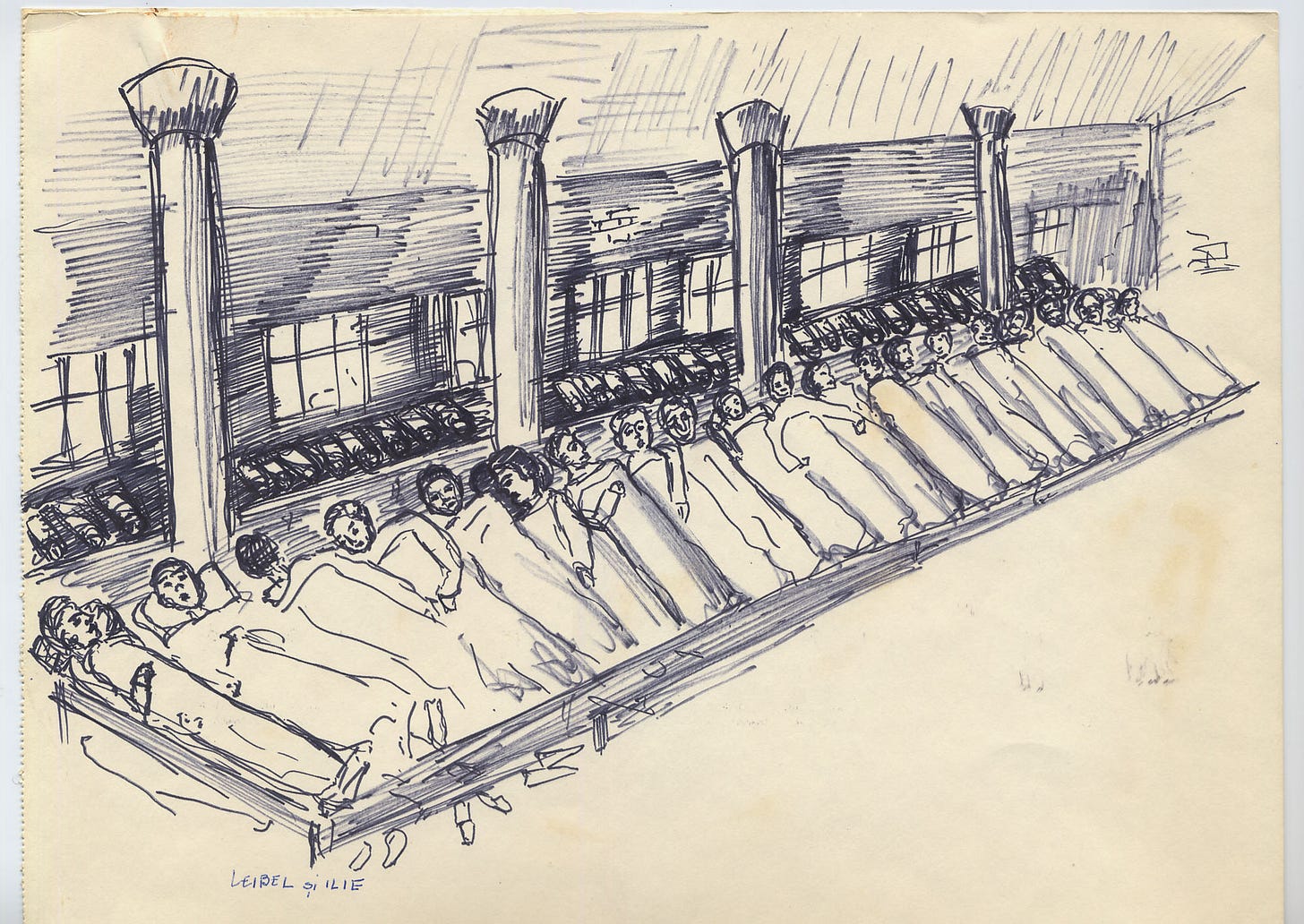

The cover of A Doctor’s Memoir features a drawing by Vapniarka inmates Moshe Leibel and Ilie Moscovici depicting deportees’ arrival to the camp. The sergeant seated at the table is smiling, likely hurling the same “insults and mockery” as before. (The drawing is in Dr. Kessler’s personal collection at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, donated by my father in 2019).

My grandfather’s memoir recalls the first appearance of the camp commandant, the future war criminal Ion Murgescu.

“He looks over the mass of men and women, talks to his people, demands that all doctors be brought to him, and departs with impressive strides.”

“One of you will become the camp doctor,” Murgescu says.

Of the 20 or so doctors among the prisoners, Kessler was placed in charge of the infirmary.

Finally, they got their first taste of decent food since their arrest and deportation.

“We delight in our first warm meal in ten days,” he writes. “Pea soup.”

Within weeks strange symptoms appeared. More and more inmates filed into the infirmary complaining of boils, ulcers, sore extremities, incontinence, excessive urination and bloating.

Soon the dying began. One patient, an elderly poultry merchant, became ever-thinner and soon expired. Another, an old peddler, followed.

Shortly after, a young man succumbed for the first time. The inmates were given permission to bury the dead on a grave-strewn hillside that the commandant had pointed to upon their arrival (“try to do better,” he had advised them).

One prisoner, a cantor, sang El Maleh Rahamim (God Full of Mercy), the prayer for the soul of the departed.

“I have heard it many times, but never before have I felt such stabs in my chest,” Kessler writes. “A loud lament, an ocean of tears, much wailing and crying. The gendarmes become quiet; even they cease to laugh.”

Before long, some of the non-Jewish Ukrainian prisoners who had been in the camp longer — a mix of POWs, common criminals and religious dissidents (Jehovah’s Witnesses) — began showing an abnormal gait.

“They walk stiffly, move their legs in awkward circles, and tire quickly,” he writes. The unfortunate Ukrainians “waddle like ducks.”

A prisoner named Avraham Solomovici started walking the same way. “He tries to walk, but sways and falls.” The next day another case appeared, then a third.

Dr. Kessler describes “a hellish, unimaginable scene: hundreds of the sick and paralyzed, gangrenous legs, loss of urine before they reach the drums, distorted posture caused by muscle contractions in arms, back, belly, and legs.”

The afflicted lay on plank beds, ten to 15 in a row.

As 1942 turned to 1943, 120 inmates were completely, permanently incapacitated and more than a thousand in the early stages of paralysis.

“It has to be the peas,” he concludes. The soup they were fed on arrival — made of peas larger and with tougher skin than the familiar type — is the staple of their meager diet.

“We are eating poison and will perish from it. Something has to be done immediately.”

He smuggled out a letter to a physician friend on the outside, who then smuggled in a medical article by messenger. It described cases from ancient times to modern, from Algeria to India and Russia. All appeared in periods of famine, all from consumption of the same pea, all with the same symptoms — limbs go black, incontinence sets in, spastic paralysis appears, breathing grows labored, and ultimately the patient dies.

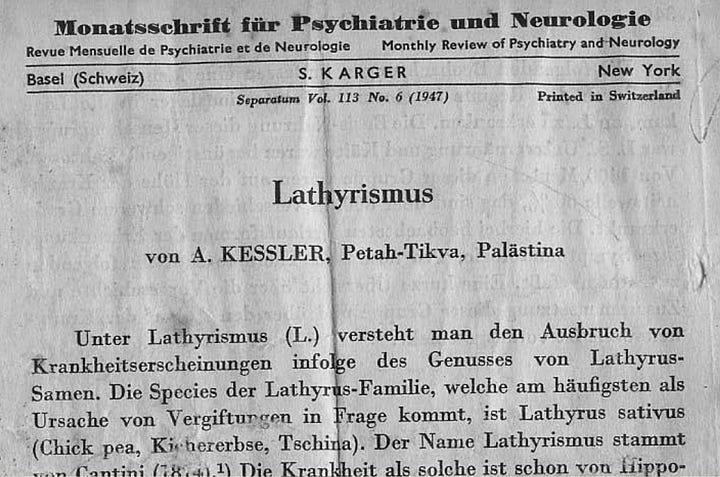

“We now know that we have eaten Lathyrus sativus” — the grass pea or chickling pea — “and have been stricken with neurolathyrism.”

By early 1943 Captain Sever Buradescu replaced Murgescu as camp commandant. Yet another “cold sadist,” in my grandfather’s words, he was even worse than his predecessor, and would demand a ring or gold watch for a glass of water (he too would ultimately be imprisoned for war crimes).

Kessler and two other physician-prisoners asked for, and received, a meeting with Buradescu.

I explain that we are prisoners in a camp during wartime, that we might be exterminated by bombing or epidemics, but that it is against international law and the duty of the state to poison us deliberately…

He listens quietly with a pinched face and replies shortly:

“How do you know we are interested in keeping you alive?”

That concludes our hearing.

It defies our usual understanding of the Holocaust that prisoners could request a “hearing” with their captors. But this was several months into the Battle of Stalingrad, as the Romanians started to wonder whether their bet on Hitler might have been a miscalculation. Moreover, authorities worried that an outbreak — typhus or typhoid — could spread beyond the prisoners to the guards and even neighboring towns.

It was those shifting dynamics that prompted the arrival of a government doctor, then a specialist, then an investigative commission in early 1943.2

Finally, the rations were changed. Prisoners showed doctors their gratitude with small gifts fashioned from whatever scraps they could find. A pin with a Star of David, another of an inmate thrusting his crutch skyward as he sprints up a hill. A “V” for Vapniarka (or is it victory?).

At last, in spring 1943, the order arrived. The regime concluded that more than 400 of the camp’s inmates — Dr. Kessler among them — were not communists and had been dumped there for no reason whatsoever.

My grandfather had spent eight months in Vapniarka. His early suspicion of the peas meant he hadn’t eaten enough of them to suffer paralysis himself.

Now he embarked on an even longer journey home — a nearly year-long odyssey through the ghettos of Transnistria — that makes up the diary’s second half. Leo Spitzer, who edited the book, hails that account as a “matchless, dramatic act of witness.”3

But for that, you’ll have to read the book.

On April 1, 1944, nearly two years after his deportation, Arthur Kessler arrived in Bucharest, where his blonde, German-speaking wife and small daughter lived as “Aryans.”

They reunited in tears. Vera, now 3, ran from door to door announcing: “A strange man has come and is kissing mother!”

Their respite lasted three days. On April 4, Allied planes began bombarding Bucharest. Romania was Europe’s second-largest oil producer, and its fuel critical to the German war machine. Hundreds of buildings collapsed and some 5,000 people were killed or wounded in just two hours of massive bombardment.

The Kesslers decided to leave Romania by any means possible.

“Palestine was an imaginable goal,” Spitzer writes, “albeit a dangerous and difficult one to achieve.”

It was not just near-impossible for Jews to escape Eastern Europe, but the British Mandate authorities in the Holy Land continued to enforce the White Paper that had all but shuttered its gates to Jews since 1939 (readers of my book Palestine 1936 will know this story well).

Through the so-called Aliyah Bet — the Zionist movement’s illegal immigration network — they boarded a small boat, the Milka, at Romania’s Black Sea port of Constanța. It was the sister ship of the Struma, which two years prior — filled far past capacity with 780 desperate Romanian Jews — had been torpedoed by the Soviets, killing everyone onboard but one.

“We climb aboard a small illegal wooden boat, taking with us a cushion and an enameled chamber pot… hanging from the child’s neck,” Kessler writes. “We remain hidden in the bottom of the boat through the first few kilometers of mined waters and then head for freedom.”

The Milka brought them south through the Black Sea, past Nazi-allied ports in Romania and Bulgaria, and finally to the upper mouth of the Bosphorus in neutral Turkey.

The relief of having fled occupied Europe, of the open skies and open sea, must have been immense. They traveled down the Bosphorus, alighting at Haydarpaşa rail station on Istanbul’s Asian side in what would have been their first time ever leaving Europe. My grandfather was 40.

Two years ago I celebrated my own 40th birthday in that astonishing city. I captured this photo of Haydarpaşa station, facing northwest in the direction from which they would have arrived. To me, the gliding bird — at bottom left, just above the Hagia Sophia — completes this frame as the very image of freedom.

At the station, Arthur and his family boarded a train that would take them east, through Anatolia and the Kurdish hinterland, then Allied-held Aleppo, Homs and Beirut, in what must have been the sharpest transition of his life — comparable only to that of the initial, terrifying deportation to the unknown.

At the southern tip of Lebanon the train passed through the white cliffs of Ras al-Naqura. A Union Jack fluttered over the border station — the “gateway to Palestine,” per an image from the time — and into the Promised Land.

In the war years it was so rare for Jews to escape Europe for Palestine (in 1942 just 2,000 arrived) that it made the local papers. When the train bearing the Kesslers and 270 other refugees from Istanbul arrived in Haifa, it was front and center in one of the main Hebrew dailies along with a list of each of their names.

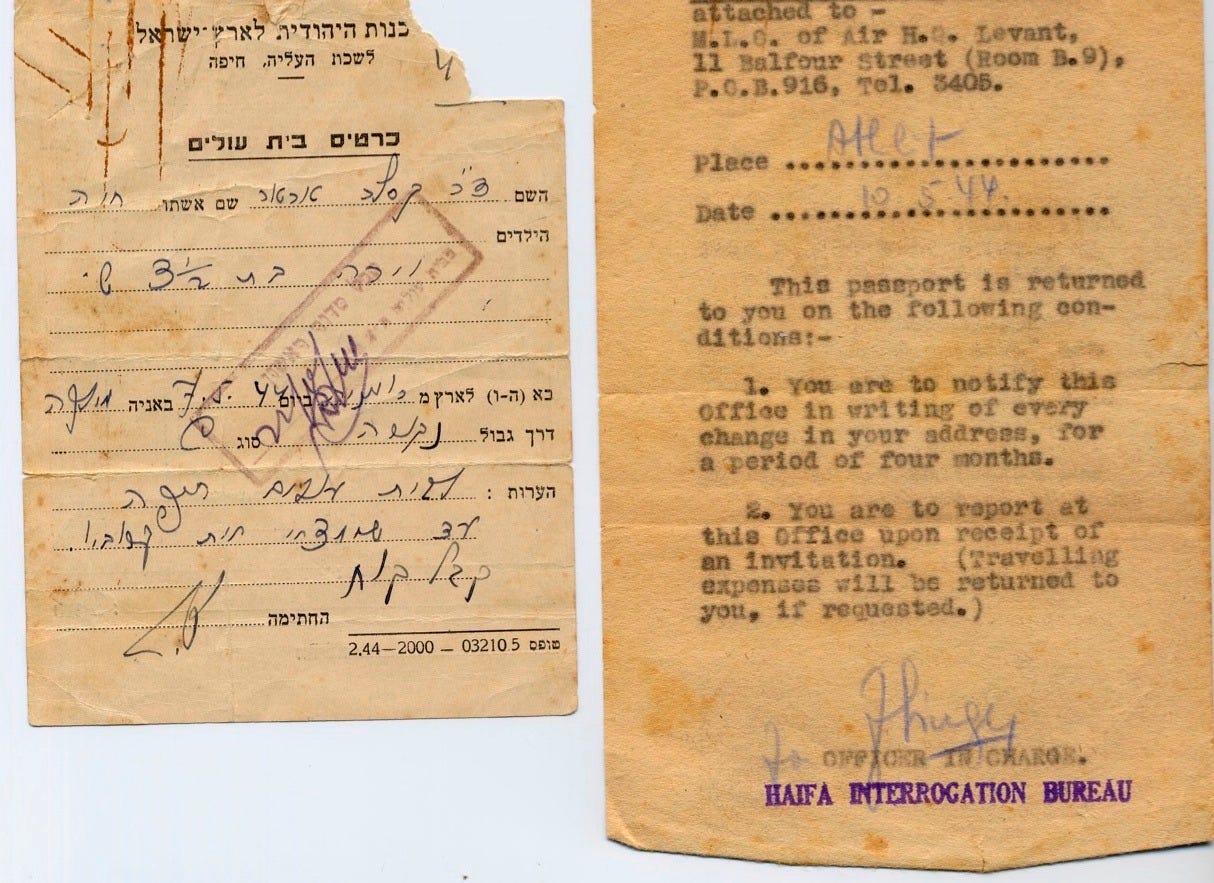

There was, however, to be one more detention and interrogation: By the British officers of the “Haifa Interrogation Bureau” — as a possible German spy.

A year later Hitler put a bullet in his skull and the war in Europe was over. Arthur’s parents and siblings had all survived, thanks largely to a Schindler-like list of 20,000 names kept by Czernowitz mayor Traian Popovici, later named a Righteous Among the Nations.

The extended family was less fortunate. On his father’s side, Arthur’s nine aunts and uncles, most of his cousins and their children — all living in Poland — were murdered, possibly in Belzec.

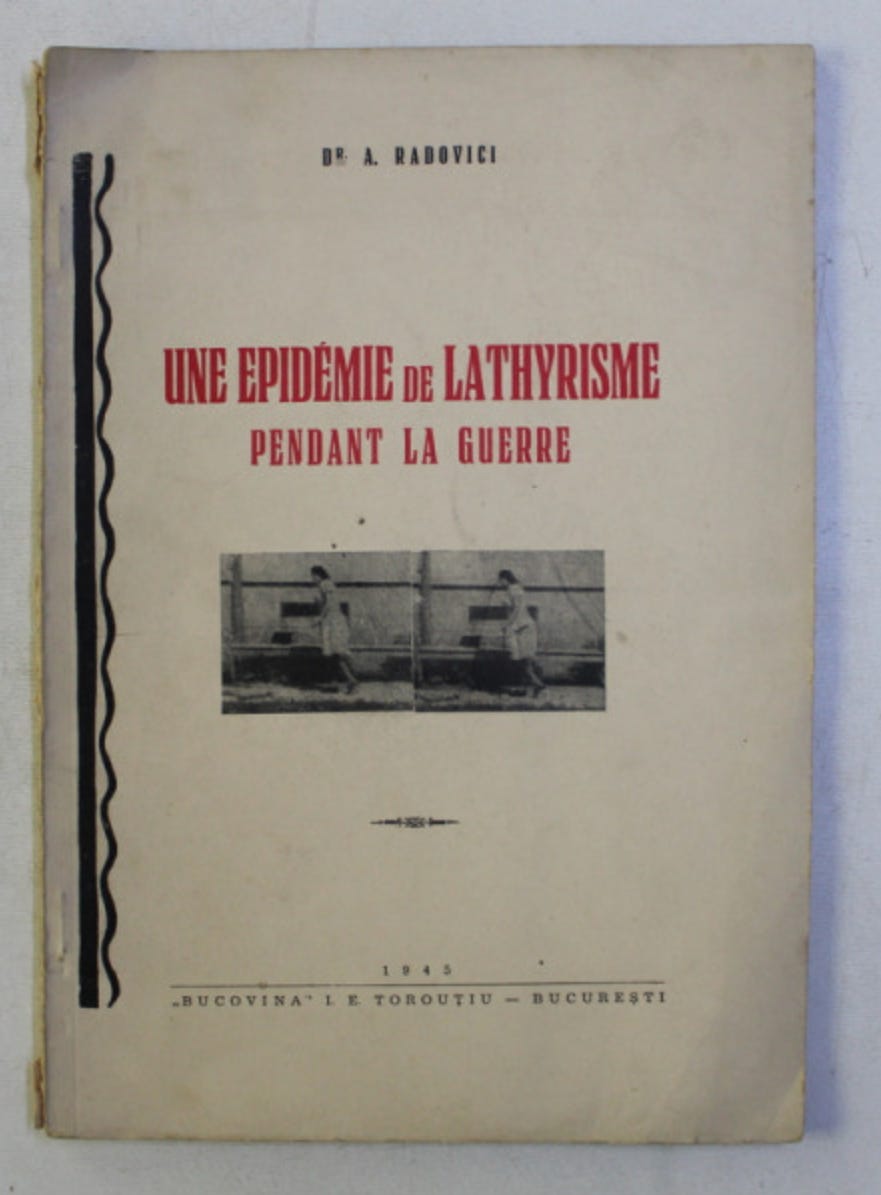

In July 1945, just two months after Germany’s surrender, a slim booklet by a Vapniarka survivor appeared in Bucharest.

Written in French, it bore this dedication:

To Dr. Kessler: An example of heroic resistance… Amidst horrible circumstances, in the “house of the dead,” he preserved the tranquility of soul and purity of spirit to scientifically trace the paraplegic epidemic known as Lathyrism.

In Mandate Palestine the Kesslers started anew.

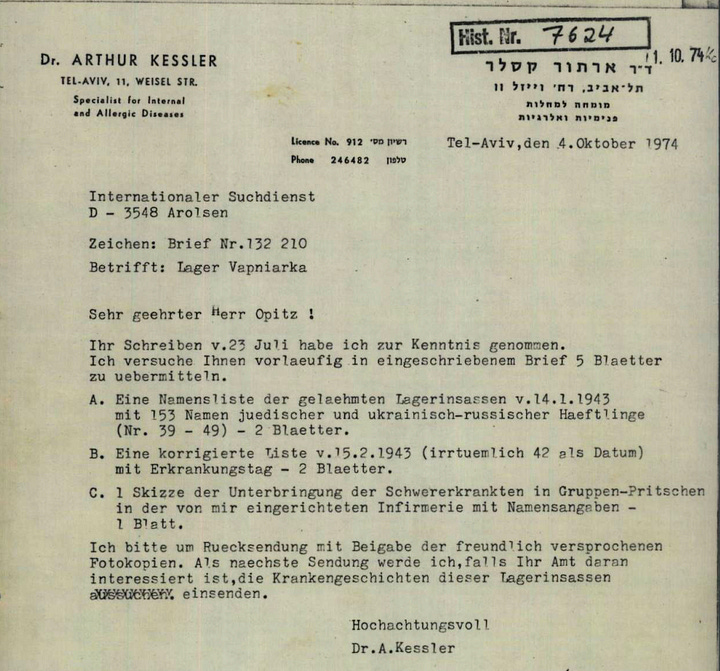

They lived first in Petah Tikva, then in Tel Aviv on Weisel Street, not far from David Ben-Gurion’s house. Dr. Kessler returned to work, at the large Clalit clinic on nearby Zamenhoff Street, where he headed the allergy department.

When war broke out in May 1948 for Israel’s independence, he took shifts treating wounded soldiers. The next month, during the war’s first truce, he and Judith welcomed a second child: My father David. He was 45 and she 39 — a nearly geriatric age to have children in those days.

Family photos show them celebrating Israel’s first Independence Day in May 1949. A newborn country, a newborn child.

In 1968 Kessler was elected chair of the Israel Association of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Throughout, he treated the paralyzed Vapniarka victims without charge in the family home.

“There was a string of people coming to our house on crutches,” my father recalled in 2000. “They had special cars, built especially for them. My dad took care of them. It was all part of my surroundings. And my father would say in German, ‘There are some things children should be spared knowing. One day the story will be told.’”

Arthur Kessler led a decades-long fight for a reparations agreement for the more than 100 Vapniarka victims living in Israel, testifying multiple times in Germany and corresponding for decades with authorities there (Romania, the primary culprit in their suffering, has never paid any reparations).

In yet another improbable turn, local Protestant church authorities near Frankfurt became involved, through the efforts of a Christian journalist named Charlotte Petersen who made the Vapniarka case her life’s mission. (An article this year by the Romanian-American scholar Olga Stefan chronicles that reparations battle.)

My grandfather was modest and shy, uncomfortable in the spotlight. Still, on repeated occasions it managed to find him. In 1972, exactly three decades after his arrest and incarceration, the government of Romania officially named him a national hero in the fight against fascism.

Judith died in 1995, Arthur in August 2000. A month before his death, my father visited Vapniarka, in apparently the first visit of any survivor or his descendant since the war.

Having been born before the automobile, he lived to see the Internet. Having lost many friends and family and himself dodged death several times, he lived to raise two children and five grandchildren and, in his 90th year, to welcome his first great-grandchild.

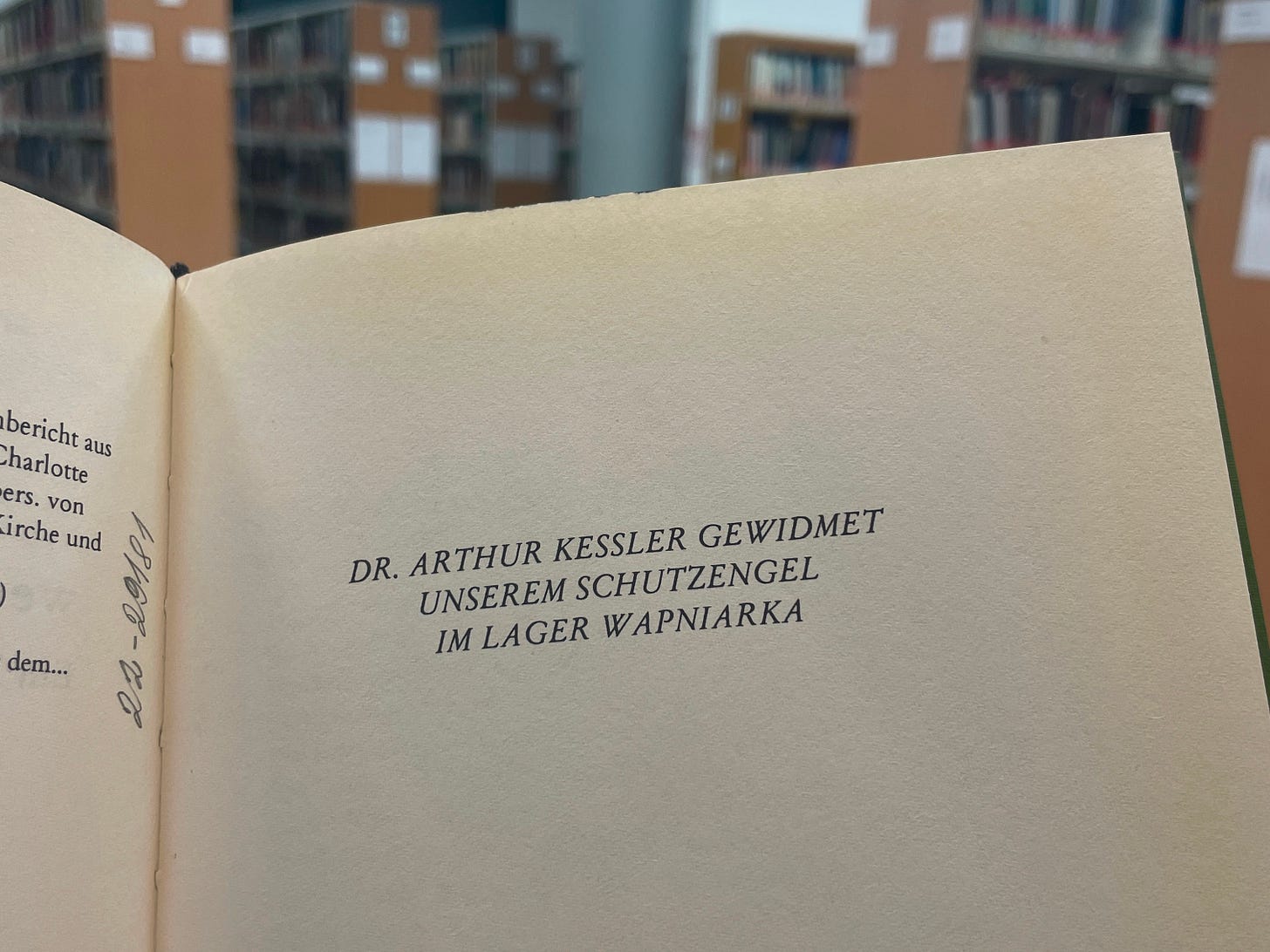

The following year a memoir was published by Nathan Simon, a Vapniarka survivor who had moved to Switzerland after the war. The poison peas had left him two-thirds paralyzed, but he had his life and was grateful for it.

The book begins with a dedication, as brief as it is poignant. It’s to a doctor called by circumstance to find the very best within himself, in both mind and spirit, in the very worst of times.

DR. ARTHUR KESSLER

OUR DEVOTED GUARDIAN ANGEL

IN THE CAMP OF VAPNIARKA

Part I of this post is here.

Since the end of World War II the city has undergone two more reinventions: First as Soviet Chernovtsy, then as Chernivtsi in independent Ukraine.

The retreating Soviets had left behind large stores of Lathyrus sativus for their horses, and the Romanians saw it as a cheap source of feeding prisoners whose lives were worth little anyway. It later emerged that certain Romanian officials had likely known the peas were lethally toxic when eaten in large quantities.

I was born in Transdnestria. Lived there until teenage years. Cute little city. My family came from Bessarabia-Jews escaping Nazis. Ended up in a former Soviet Union and eventually ended up living in Trasdnestria. My grandfather told me a story about how he ended up in that region. When he was 13 years old my great grandfather who was his main caretaker and a doctor send him off on a train with Rusians, who at the time were helping Romanian Jewsh escape Nazi's genocide. The great grandfather staid behind, and my 13 year old grandfather that spoke zero Russian ended up in Sovet Union. When he was in his twenties he decided to relocate to Transdnestria, citing that he really loved how beautiful the city is as one of the main reasons of ending up there. I had no idea about the camps in Transdnestria until I read your article! Now it makes me wonder if one of the main reasons he ended up there was in search of his grandfather or some traces of him. Or possibly get closure. The only understanding that I got from him of what happened to my great grandfather was that he was killed by Nazis but no detail on how. Thank you for sharing this!

amazing history