Yolande Harmer: Israel's forgotten super-spy in Egypt

Harmer was Israel's most important spy in 1948, infiltrating the royal palace, Muslim Brotherhood and Arab League. Her legacy deserves to be honored

Quick note: I try to keep these on the short-ish side, but once I dip into the archives the word count tends to slip my grasp. My genuine apologies — feel free to just look at the photos. Or get the Substack app, where an AI will read this aloud while you do the dishes …

Ask Israelis to name their country’s most famous spy and the responses are typically fairly consistent. First is invariably Eli Cohen, who infiltrated the Syrian regime’s uppermost echelons before he was exposed and executed in Damascus’ central square. Second is often Rafi Eitan, who led the squad that seized Adolf Eichmann from a Buenos Aires sidewalk and delivered him to trial, and ultimately the gallows, for his crimes. A distant third may be Wolfgang Lotz — a suave, blond (and, usefully, uncircumcised) agent posing as an ex-Nazi horse breeder who revealed the darkest secrets of Egypt’s missile program.

One name you almost certainly won’t hear is Yolande Harmer. But Harmer was Israel’s most valuable spy in its 1948 war of independence, penetrating the Egyptian royal palace, the Muslim Brotherhood, the Arab League and half a dozen foreign embassies in Cairo — and all with rare courage, energy, ingenuity … and style.

Few spy tales are as captivating, and few are as tragic. Less than a decade after registering some of the most impressive feats of modern espionage, she died in Jerusalem, cast aside and forgotten, at 46.

Out of Egypt

She was born in 1913 in Alexandria as Yolande Gabbai, the daughter of a Turkish-born mother and a father from Livorno, Tuscany.

Though Egypt was then under British rule, the city was a cosmopolitan hub — immortalized in Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet and Aciman’s Out of Egypt — a tenth of whose residents were foreign-born: Greeks, Italians and French; Levantine Arabs; Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews.

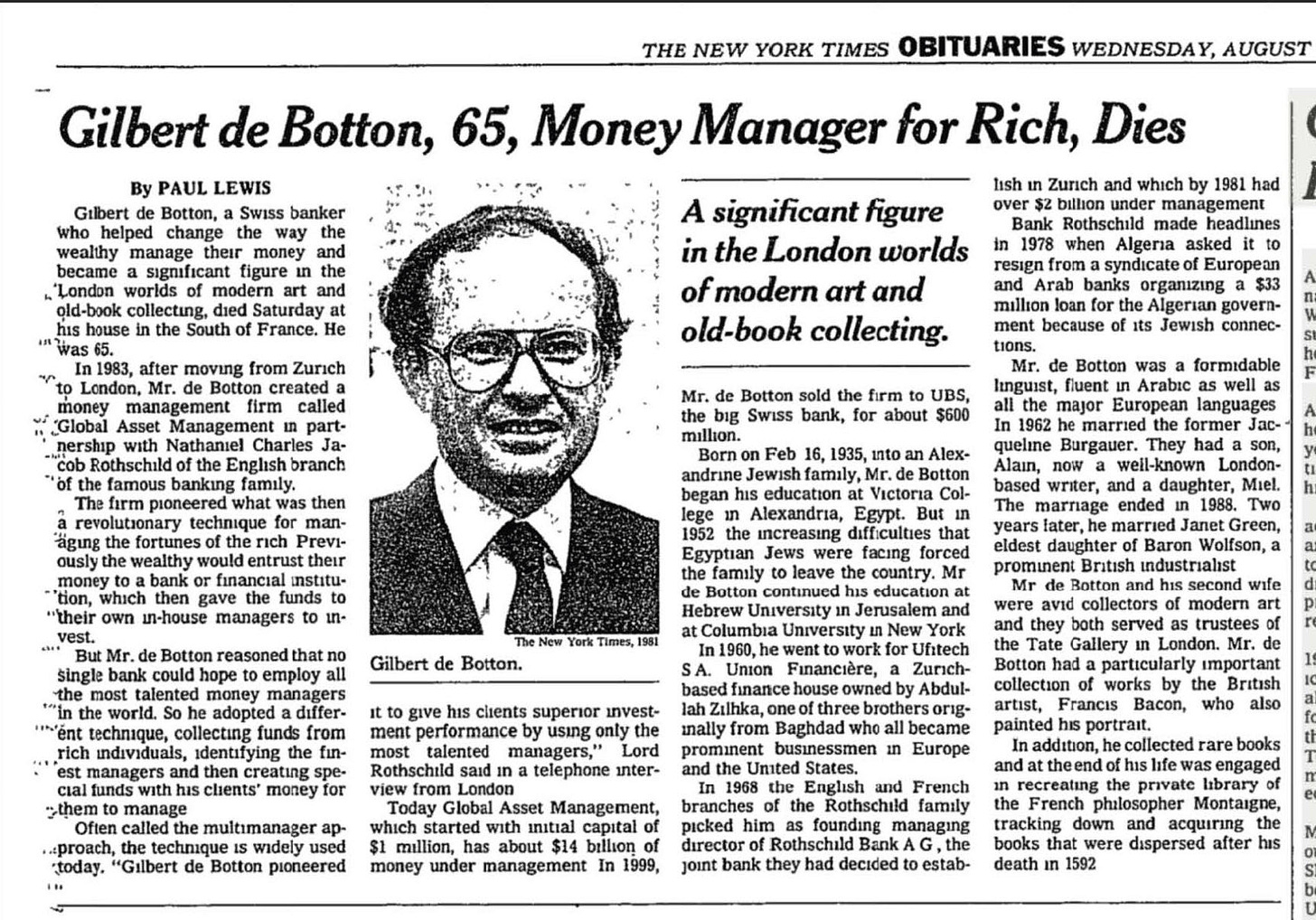

She married three times. The first, arranged when she was 17, was to Jacques de Botton, an oil company representative whose ancestors hailed from the Spanish town of Botón.

A son was born in 1935 and given the French name Gilbert, but the couple separated while he was still an infant.

The name of her second husband remains a mystery, but her third husband was Harry Harmer, a South African pilot whose plane was shot down in the Second World War. He had been the great love of her life, and she carried his name for the rest of her years.

“It was a terrible blow to her,” Gilbert later recalled. “Romantically and affectionately, she never recovered.”

A web of admirers — and sources

Harmer’s introduction to Zionism came in a 1942 lecture in Cairo by the Italian-born Enzo Sereni. She was, per the author Joshua Tadmor, “captivated by his courage and charm. His strong feeling for Palestine awakened in her a desire to visit the Promised Land.”

Later that year, as Hitler’s Panzers stormed through the Egyptian desert, she fled to Mandate Palestine with Gilbert — their first-ever visit. She met Zionist leaders like Moshe Sharett, de facto “secretary of state” of the Jewish Agency proto-government there (and later, Israel’s first foreign minister) and Eliyahu Sasson, the Damascus-born chief of the Agency’s “Arab Department.”

On her return to Egypt she began work as a reporter for the Palestine Post and Jewish Telegraphic Agency. But in 1944, Sereni was parachuted into his native Italy in a secret British-Zionist operation and was captured and executed by Fascist forces. Harmer was gutted.

In June 1945, weeks after the Allied victory in Europe, Sharett visited Cairo to discuss Palestine’s postwar future. It was at a cocktail party in the Egyptian capital that he recruited her as a spy.

“I have a picture of Yolande dancing,” a friend reminisced in the 2010 documentary Yolande: An Unsung Heroine, directed by Dan Wolman and produced by Harmer’s granddaughter Miel de Botton. “Very petite, dressed in this very feminine way, very high heels, and totally, completely connected to the person she’s dancing with. I thought, ‘Who is this Yolande?’”1

“She was — beautiful isn’t even the word,” remembered another friend. “Terribly feminine. Dressed in a very simple way but very elegant. Smiling, but not with her face — she was smiling with her whole body.”

In the film, a colleague recollected how she met Egypt’s King Farouk.

We were dining in a Cairo hotel. Suddenly everything went quiet — the king had arrived to have dinner. Suddenly Yolande got up and started walking towards him. When she passed by his table she burst into loud laughter that filled the whole hall.

She spoke to him directly: “Please excuse me, you can arrest me if you want. But this is the only way I could reach you. Many times I’ve asked Your Highness for an interview and never got one — what will I write to my paper in America?” The king got up, extended her hand and gave her his card. That’s how a fantastic connection was made with the Royal Court.

Her suitors included Takieddin (“Taki”) el-Solh, deputy director of the Arab League and Lebanon’s consul in Cairo (and, decades later, the country’s prime minister). In the film, Harmer’s assistant said flatly that Solh was “in love with her.”

The historian Yoav Gelber writes that among those smitten by Harmer was also Taki’s older cousin Riad el-Solh — independent Lebanon’s first prime minister. Harmer “was proud of the compliments she received” from Solh and other Arab dignitaries, Gelber writes cryptically in the Hebrew journal Cathedra.

Her admirers also included Mahmoud Makhlouf, son of the Mufti of Egypt. In late May 1948, just days after Israel’s birth, a Zionist intelligence report marveled that the younger Makhlouf (codenamed “the Prophet”) “devotedly sends Harmer information without any compensation.”

Yet another aspirant to Harmer’s affections was Sweden’s ambassador in Cairo, Widar Bagge. “Several months ago he was indifferent to our cause, but today he is an enthusiastic Zionist,” the report gushed. “Some of the information on the Egyptian army came from him.”

But four months later, the first UN Mediator for Palestine — Bagge’s fellow Swede, Count Folke Bernadotte — was assassinated in Jerusalem by members of the militant Zionist faction Lehi. The ambassador never supplied her with intelligence again.

‘Israel’s best spy’

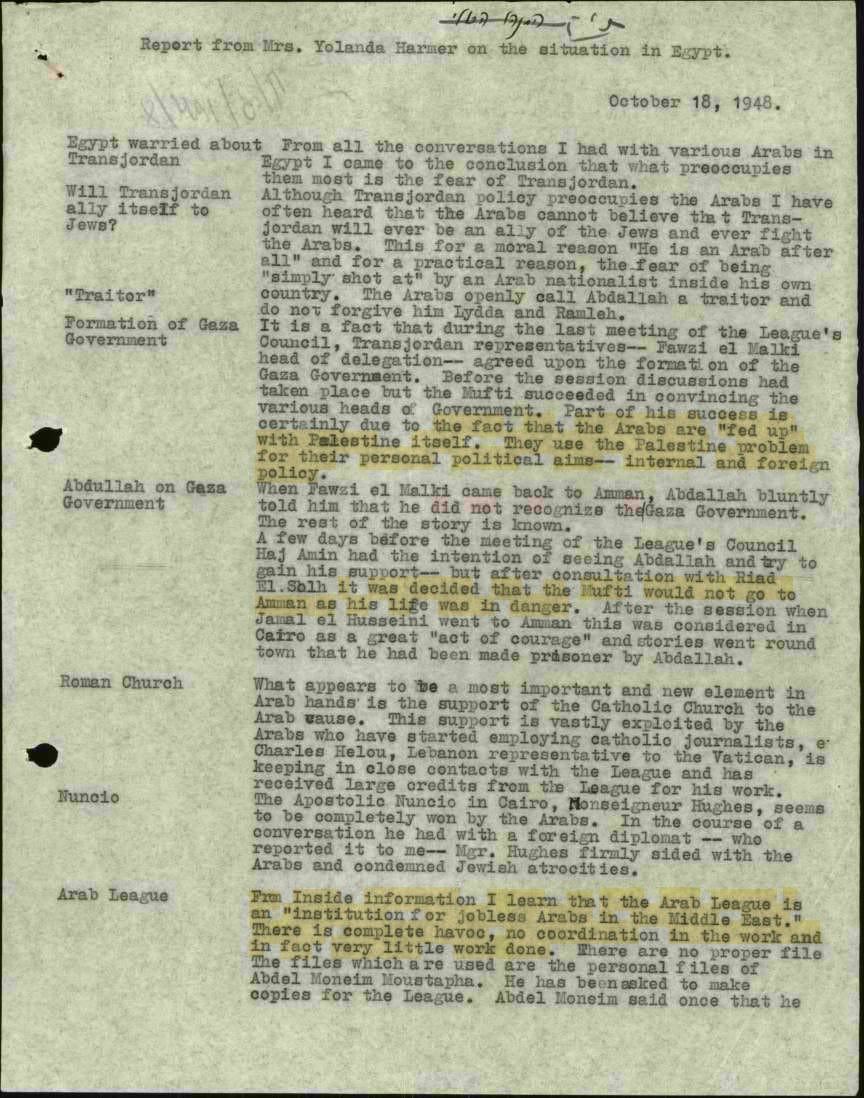

Admirers notwithstanding, it would be wrong to typecast Harmer in the role of seductress. From 1945 to 1948 she was deeply involved in the most sensitive intelligence operations and, under the codename Nicole, sent hundreds of dispatches to Palestine.

In the documentary, an emissary from Jerusalem recalled their first encounter at her Alexandria apartment.

“Through Yolande’s front door I heard her childish laughter. She said, ‘Come, habibi, sit down and I’ll tell you why you’ve come to Egypt: To get weapons left behind by the Germans.’” They located a remote “lover’s nest” in the countryside and turned into a depot for the transfer of Nazi weapons, stolen or bought illegally from the British, across the Sinai to the Holy Land.

“Yolande Harmer was probably Israel’s best spy in 1948,” write historians Benny Morris and Ian Black in their book Israel’s Secret Wars. “She was the most prominent and effective of the agents who had been run since the mid-1940s by the Arab Division of the Jewish Agency.”

“Yolande Harmer was probably Israel’s best spy in 1948”

Her contacts extended into British officialdom in Cairo, including the head of the police detective office (codenamed the “Helper”) and the local branch of MI5. She had sources in the Polish and Soviet delegations there, and obtained secret cables sent by the charge d’affaires of the U.S. embassy as well.

She was equally entrenched in Egyptian circles, with sources in the Muslim Brotherhood, the pro-fascist Young Egypt party, and the country’s top newspaper Al-Ahram. Starting in 1945 she met at least three times with Azzam Pasha, the first head of the Arab League that was founded that year in Cairo.

The following year she learned that Jamal Husseini — a relative and ally of the infamous Mufti of Jerusalem Hajj Amin al-Husseini, himself newly arrived in Cairo from Hitler’s Berlin — had persuaded the League to start planning military operations against the Jews of Palestine.

A year after that, she learned that the League had gone further, allocating funds for armed fighters loyal to Hajj Amin, and declaring that “they would sacrifice all the political and economic interests of the Arab world, in order to save Arab Palestine.”

In early 1948 Taki el-Solh provided her with precise Arab League resolutions over the Arab states’ intended invasion of Palestine should the Jews declare statehood. Most valuable of all, he provided her detailed plans for the Arab Liberation Army — a volunteer force created by the League and commanded by Fawzi al-Qawuqji — to invade Galilee and Samaria.

That particular piece of intelligence came at a cost of 300 Egyptian pounds — a huge sum at the time. Once the payment was greenlit, Harmer sewed the resolution into her shoulder pads and flew to Lydda airport to present it personally to Jewish Agency chief David Ben-Gurion.

In an interview with Wolman from the 1990s, Gilbert reminisced about her mother’s flight to see “BG,” the purpose of which he learned many decades after her death:

Prison to Paris

Ben-Gurion’s declaration of Israeli statehood on May 14, 1948 marked the beginning of the end of Harmer’s espionage work. In the weeks after, hundreds of Jews suspected of Zionist ties were arrested.

“My condition here is very tenuous,” she wrote to Sasson five days after Israel’s birth. “I’m still ‘out’ thanks to the influence of a few friends. If you think I could be more useful somewhere else, I wouldn’t oppose a change of air."

Two months later it was all over.

“Yolande has been arrested,” Sasson cabled. “‘The Prophet’ behaved very badly, and ‘the Helper’ is saving his own skin. As for Taki, he’s pretending ‘he knows not Joseph.’”

She served a month in prison, but her endless contacts meant her conditions were notably lax: She was allowed daily newspapers and ordered delivery from Cairo’s finest restaurants. She was freed after a month, possibly because the Egyptians hoped she could be useful in postwar talks with Israel. Or possibly because her health had begun failing, badly.

“She became very thin, very pale, but with a smile,” remembered a friend. “Always with a smile.”

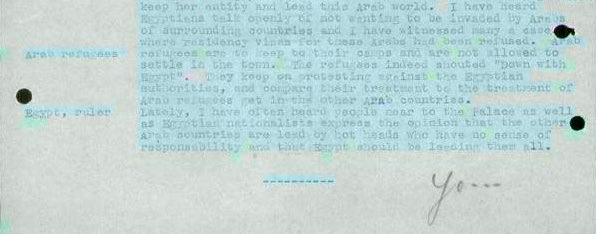

Released from prison, Harmer flew directly to Paris. There she wrote a detailed and insightful portrait, in English, of an Egypt undergoing rapid transformation.

Before the Arab League’s creation, she wrote, Egyptian identity and culture had been distinctively “Egyptian to the point that calling an Egyptian an Arab was an insult.”

But the three years since had brought the end of the cosmopolitan Egypt where she had lived her entire life, and a new obsession with “Egyptianization.”

“The creation of the League, the arrival of the Mufti [of Jerusalem], the Palestine war and Arab propaganda have brought Egypt to merge in the Arab world,” she wrote. From now, some foreigners in Egypt may be tolerated “as useful elements” but never allowed to gain prominence of any kind.

That reality held dire consequences for the 50,000 Jews of Egypt. “It is a fact that anti-Semitism in the form it takes in the West does almost not exist” in the region, she wrote — a striking observation given the Arab world’s dubious distinction as the world’s leading locus of anti-Semitism in the decades since.

“The Arabs are ‘fed up’ with Palestine,” she added. “Still, Arab propaganda and the use of anti-Zionism as a national slogan have rendered the future of the Jews most precarious.”

“Fifty-thousand people are condemned to slow starvation,” she concluded. “Unless a miracle happens there is no future for the Jews in Egypt.”

Into Egypt (again)

The French capital was home to a new intelligence network, the “Paris Branch,” that Israel had established in its first months of existence. The choice of location had a certain logic — in late 1948, as the United Nations began construction on its permanent New York headquarters, the city played host to the 3rd UN General Assembly.

It was in Paris that Harmer discarded her journalistic cover and began representing Israel — first in private, secret meetings and then, increasingly, in the open.

“My mother immediately became active with the Israeli delegation to the UN,” Gilbert recalled in the film.

On the Arab side the atmosphere was that she was one of them, rather than somebody from the other side. But one of them who was also a Jewess — they respected her loyalty to the other side, which she never hid, but they also believed in her sincere affection for them.

She pursued feelers with Cairo over a ceasefire and potentially even a peace deal. Still, any such hope was dashed when Egypt suffered humiliating losses to Israel in the Negev that autumn (Operations Yoav and Horev) and Muslim extremists assassinated its prime minister by year’s end. Stepping out of the Arab consensus against peace with Israel now looked increasingly unlikely.

It seemed Harmer’s work was over. Incredibly, she decided to return to Egypt.

“When one looks back historically, one wonders how one could possibly have thought of this,” Gilbert acknowledged. “It was completely bizarre, in retrospect, but even more bizarre that it did not seem bizarre … her friends all welcomed her back, and even some of the Egyptians whom she saw in government circles.”

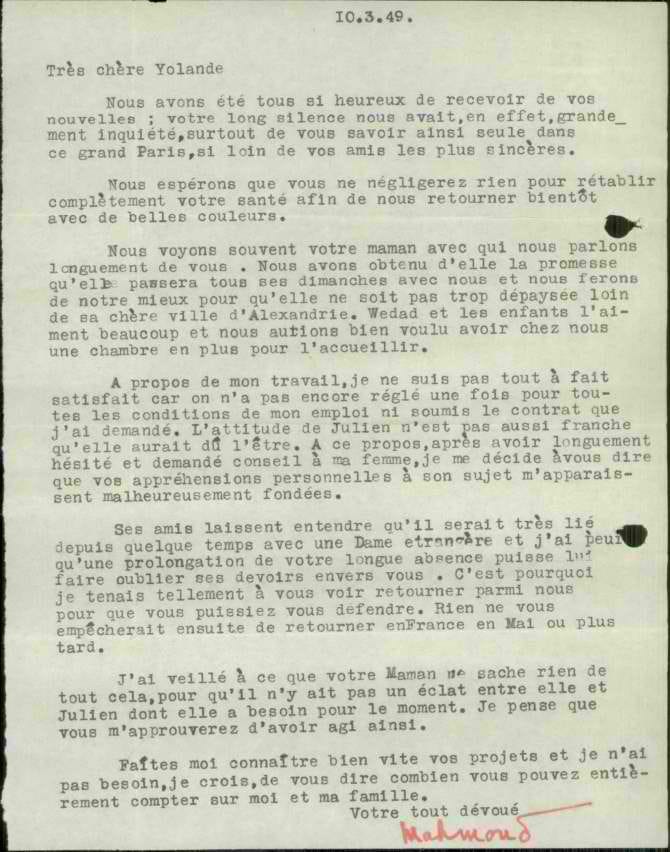

The Israel State Archives holds a remarkably warm letter addressed to Harmer, in French, from Mahmoud Makhlouf — the mufti of Egypt’s son — from March 1949, just weeks after the armistice between the two countries.

Dearest Yolande

We were all so happy to hear from you. Your long silence had indeed worried us greatly, especially knowing you were so alone in this great Paris, so far from your most sincere friends.

We hope you will do everything to fully restore your health so that you can return to us soon with beautiful colors ...

Let me know your plans quickly, and I don’t think I need to tell you how much you can count on me and my family.

Yours sincerely, Mahmoud

Exodus and disillusion

By 1951 it was apparent the Harmers’ Egyptian idyll was over.

“It was pretty clear that our days in Egypt were up, and that we were going to go to Israel,” Gilbert said. “My mother was brave, not depressed. She didn’t express nostalgia for the wonderful life of Alexandria, or that we could have been in Paris. She was not that type of person.”

They moved into a small apartment in Jerusalem’s Katamon quarter. She began working as a clerk in Israel’s Foreign Ministry, and Hebraicized her name to Har-Mor. But just as the new Egypt had no room for the Harmers, in the new Israel Yolande soon found that she too had become, in Gilbert’s words, “marginal.”

A friend recalled how some colleagues perceived her: “She’s not one of us. She’s not Israeli. She speaks strangely and has these European mannerisms. The Sabras laughed at Europeans, and she was very European despite being from Cairo.”

“She was coquettish when Israeli women went with short pants,” said Vittorio Dan Segre, an Italian-born Israeli diplomat. “She was elegant when elegance was seen as a sign of decadence. She was refined and gentle in a place where people wanted to be seen as hard pioneers.”

She was individualistic, free-thinking, politically dovish and wholly comfortable with Arabs — at a time when the predominant Israeli culture was none.

“Ce n’est pas juste”

As her relevance was fading, so too was her health — by now it was apparent she had cancer. The feeling that her efforts on Israel’s behalf had gone unrecognized only added to her pain.

“Ce n’est pas juste,” she told a friend who visited her in hospital.

In her final months, friends finally wrangled a letter of accreditation recognizing her as an Israeli diplomat — a symbolic nod to all she had done in the country’s critical hour.

Gilbert was a graduate student in economics at New York’s Columbia University when he learned his mother was near death. By the time he landed in Israel, he was too late for the funeral. She died on February 16, 1959.

Her headstone in Jerusalem bears only her name, written in Hebrew.

Four decades later, next to her former flat in Katamon, a square was dedicated in her honor. Its Hebrew inscription is similarly understated, offering merely a glimpse into her accomplishments:

“From 1945, Yolande Harmor worked inside Egypt towards the establishment of the State of Israel.”

Coda: Of lineage and legacy

Yolande did not live to see it, but her spirit — call it resourceful resilience — lived on through her family in ways she could not have envisioned.

After Columbia, Gilbert became a banker and art patron in Zurich and London. He co-founded Global Asset Management, which pioneered the “open architecture” model of money-management for the ultra-wealthy (the New York Times explains it better than I could). Starting with $1 million, Gilbert sold the company to USB in 1999 for $600 million.

He left behind two children with his first wife, Jacqueline: Miel and Alain.

Miel — whose middle name is Yolande and who bears a striking resemblance to her grandmother — is a certified clinical psychologist. Like her father she is also a philanthropist — in Israel she is closely linked with the Weizmann Institute of Science, where two research centers carry the family name.

A decade ago, she shifted to a very different path, pursuing her dreams of a career as a singer-songwriter. Since then she has built up a devoted fanbase — with nearly 20,000 followers on Instagram alone — and performed with artists from Wet Wet Wet to Simply Red.

Alain de Botton, her younger brother, is the author of more than a dozen books, including Religion for Atheists, The Consolations of Philosophy and the international bestseller Status Anxiety. Two decades ago he spoke to Haaretz about his grandmother Yolande:

My grandmother really died, not literally, but her spirit was broken by working for the State of Israel. It is particularly heart-breaking. Operating in Egypt, she was motivated by a feeling that Jews should have a homeland.

She came from a generation where living with Arabs was completely natural. The Jewish community of Alexandria was extremely integrated, my father grew up speaking Arabic with Arab children. There was a sort of insight that has now been lost — there were Jews of that generation who had a cosmopolitan view that many Israelis don’t have.

“There was a dream of a free Israel that she wanted to pursue,” Miel told BBC Radio in 2016.

“She was a remarkable woman, a woman raising her son on her own, taking huge risks for a cause she believed in. And it was a beautiful, peaceful cause,” she said. “She deserves to be remembered.”

The film Yolande: An Unsung Heroine is no longer available for individual viewing online; I’m grateful to filmmakers Dan Wolman and Miel de Botton for generously providing me with access.

Maybe time for a feature film. Do you write screenplays?

This was such a fascinating read, wow! And I had no idea that Yolande was the grandmother of Alain de Botton. Thank you for having „unearthed“ this and brought to the attention of a wider audience.